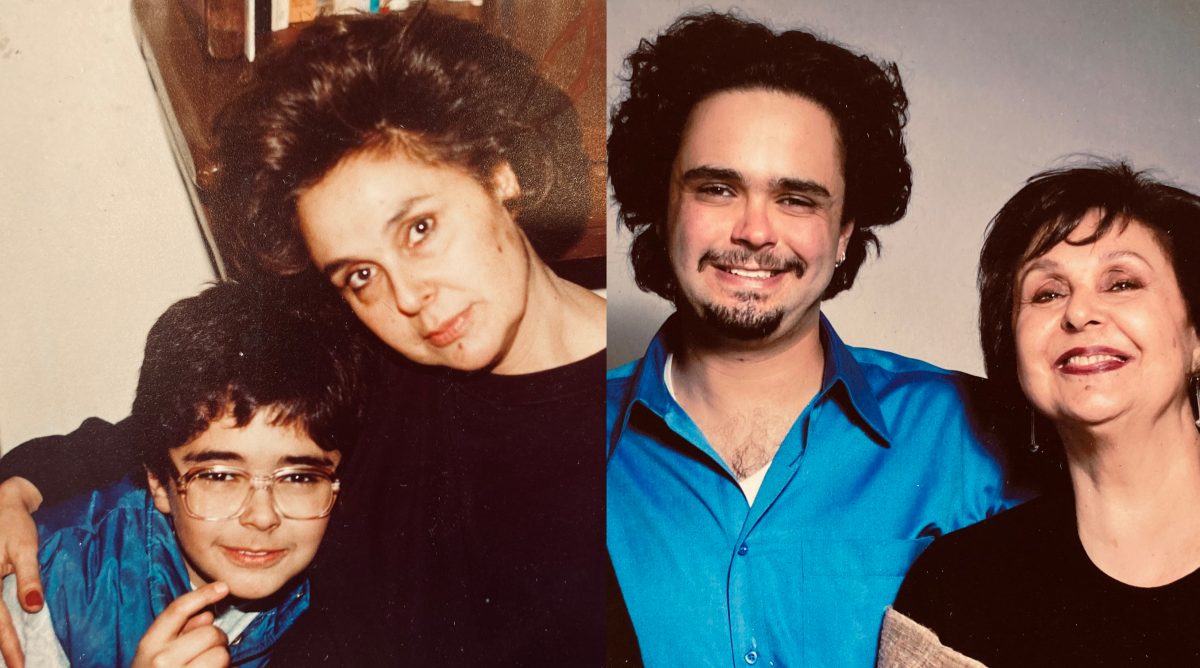

Nidal Al-Achkar, the ‘Grand Dame of Lebanese Theater’ has had one of the most storied careers in Middle Eastern acting history. The accomplishment she may be most proud of though, is the one closest to her heart—her son, the acclaimed film director Omar Naim.

Her career achievements, however, need to be underlined: Nidal, 76, is perhaps the most influential voice in modern Lebanese theatre, a vital and progressive voice that made theatre something that was accessible to all.

She directed her first play in Beirut in 1967, founded the Beirut Theatre Workshop in the late 1960s, and, though she was forced to leave the country during the Lebanese Civil War, once the war ended, she returned and founded the Medina Theater in 1994.

For her many gifts to the theatre world, she has been given many awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2012 Murex d’Or, one of Lebanon’s highest honours.

Omar Naim, born to Nidal and her husband in 1977, became fascinated from a young age with film, and equally in awe of his mother’s work, making his first documentary about her theatre, Grand Theater: A Tale of Beirut, as his thesis at Emerson College.

At the age of 25, Naim directed The Final Cut, a sci-fi drama starring the great Robin Williams that was years ahead of its time, doing what Black Mirror tried to do a decade later with more heart and soul. Since then, he’s continued to direct, releasing the horror film Becoming on 2020 before coming to the UAE in 2021 to film the Saudi-set epic The Empty Quarter, which he just wrapped principal photography in Abu Dhabi.

Esquire Middle East spoke to Nidal and Omar about their relationship, and how the two have supported each other to become the people they are today.

Happy Mother’s Day, everyone.

Read the full interview below:

The mother-son relationship is a very powerful one. At what point did that turn from a dependent one, into a mutually supportive one?

Omar: I knew I wanted to be a film director at around age 13. My mother being a director and actor gave me a sense of how rich that life could be, but also how challenging. She never pushed me toward this work, but when she saw me drawn to it, she supported me from the beginning. She never tried to talk me out of it, even though really the wise thing to do is to talk someone out of it, because it is a painful path especially in the Arab world. Since I left for film school, my mother has been one of my key creative confidantes. She’s read every script, we discuss every movie, and most importantly, I trust her instincts about actors. Whenever I am considering an actor, I show her, and she can size them up immediately.

Nidal: I always read Omar’s scripts, and learned a lot from his style that I applied to the theatre. One of the major changes I made in Rituals of Signs and Metamorphses, a play by Saadallah Wannuos that I directed, was to cut the long dialogue scenes and replace them with visual sequences. This is something cinematic that I learned through Omar, from the rhythm of cinema, and it gave my work a new energy.

Omar: What can I say? I owe everything to my mother. Her love of the arts, her passion for social justice, her belief in me and my career. Even though I made my career in the States, where I couldn’t literally build upon her success, I have always been standing on her shoulders.

Nidal: I’ve always supported Omar, because I am aware that most people don’t understand how difficult this profession is, how complicated. From the beginning, I liked his peculiar sense of humour, and his unusual talent. I admire the fountain where all his crazy ideas come from.

What are the other ways you empower one another?

Nidal: By loving, by giving, by being there when you are needed. Supportive. But also, critical when need be. It’s true Omar is my son, but he’s also my friend, ever since we became partners in choosing our professions.

Omar: It’s hard to say, but one of the ways my mother empowered me was to let me go. To move away from Lebanon, to make a life and career in the States. She knew I would have more opportunities there, especially since English has always been my strongest language. She let me go, even though it was very painful for her as a mother, and for me as a son, because she knew that’s what I needed as an artist. This is her greatest gift to me, her greatest sacrifice. Now that I am a parent I really understand how big a sacrifice it was.

What do you admire most about the other?

Nidal: Perseverance. He’s talented and he’s stubborn. He always finds a way to get things done. He also has a great relationship with people, different people from all walks of life. He knows how to keep friends and grow a beautiful network. He helps other people too, I like that about him. But the thing I love most about Omar, that touches me most, is not only his talent and creativity… I like his deep love and tenderness. Although he has been in the US for more than 25 years, he’s still an Arab, deep inside of him. So I say to myself, I did something right, bringing up this kid.

Omar: What I admire most about my mother creatively is her conviction in her ideas. She doesn’t allow negativity into her mind. She takes criticism but doesn’t let it wound her. She loves new talent and is always looking for young energy. As a person, what I admire most about is her kindness, her endless generosity. I never saw a person, from any walk of life, who asked for her help and she refused. She always used position as a star to help the needy.

How do you speak to each other about one another’s work, or is that something you keep totally separate?

Nidal: We talk very regularly and directly. We try to help each other with constructive criticism, as he will get enough negative feedback from all over.

Omar: In the early stages of my mother’s plays, when she’s still conceiving the work, that’s when we have most of our discussions. I ask questions about the narrative and the ideas, and we have very frank exchanges. I have some experience as a writer of drama at this point, so it’s fun to workshop ideas and discuss different dramatic possibilities.

Do you feel that gender equality is improving in the region?

Nidal: No. It’s becoming worse, because of fundamentalism and sectarianism and racism. A woman is not paid as well as a man, she doesn’t have freedom of travel, she doesn’t have the same opportunities. Women are tied into tribal laws and family entanglements. That’s because we don’t have citizenship in the Arab world, where the same law applies to everyone. Here in Lebanon, for example, we don’t have civil marriage. Without something fundamental like that, how can you have equality? The woman who is oppressed in the Arab world is our mother, our sister, our daughter, our aunt. Why do men want oppressed and unhappy women to live with them? This is a big question about men’s psychological behaviour.

Omar: There are minimal improvements, but honestly the state of gender equality in the region is a disgrace.