Ramy Youssef is still riding high on the massive successes of tv shows Ramy and Mo, but with the end in sight for his signature series, the multi-hyphenate is setting a new course for his career and life

Ramy Youssef is not one for beginnings.

“I always notice, whether I’m on stage or in the show, my beginnings are a little slow. I tend to set up a bunch of things that start to connect later,” Youssef admits.

It’s no wonder, then, in an era when everyone is rushing to be the first of something, Youssef isn’t interested in firsts. Firsts are just other beginnings. Sure, his award-winning series Ramy may be the first American series to centre an Arab family, and the first to grapple with what it means to be a practicing Muslim in the 21st century, but, to him, it is just a foundation. With those now laid, the real work can begin.

“People are so obsessed with breaking ground, they forget that you break ground to build something,” I suggest, distilling a bunch of what he’s already said better.

“Exactly,” Youssef encourages.

The two of us are having breakfast at the Cobble Hill Coffee Shop in Brooklyn, New York. It’s the first time we’ve met in person after years of Zoom calls. Luckily, there’s no ice (or ground) left to break. I’m wolfing down enough corned beef hash to instantly undo the months I’ve spent eating healthy, and he’s nestled in a cozy looking orange wool jacket having egg whites and tea, grinning like a proud and contented papa as the seeds he’s planted creatively have started to sprout.

After our breakfast, Youssef will head to the Gotham Awards along with Palestinian comedian Mo Amer, where the duo will present one award and perhaps unexpectedly pick up one of their own—breakthrough series for Mo, the Netflix show the two of them co-created.

“Mo is the part of the beginning of something for us,” he tells me. “My production company that started to grow out of this is called Cairo Cowboy, and I knew as soon as we shot in Cairo in season one of Ramy that there was this rapidly inevitable future coming where point-of-view is going to be centred from everywhere. We have an opportunity to be a part of that.”

Our conversation jumps all over the place as usual, but it’s clear in the two hours that we talk that Ramy the series—the show that catapulted him into a new level of stardom; won him a Peabody Award and a Golden Globe for Best Actor; a show coming off its best, funniest, and most focused season yet—is something he’s already looking past.

“We’re trying to find a good conclusion for Ramy now,” he says off hand at one point.

“You think there’s a couple seasons left, maybe?” I ask.

“No, season 4 is the final season,” he confirms.

“Really?”

“Yeah. Honestly. It’s December [2022] now, right? This time in 2016, I had just finished putting together the characters and everything for the show. That means it’s been on my mind every day for a pretty long time. So we’re going to do one more swing, and then in the end it will have been a good seven years of my life,” Youssef says with a laugh.

Youssef is beyond proud of what he and his many collaborators have created with the series, but he’s ready for a change. Part of that is because of how he’s seen the world change.

Growing up, he keenly felt there was a lack of his experiences represented on screen—“and the gap wasn’t as black-and-white as there’s no Muslims on TV. It’s that they’re third culture kids. There weren’t characters who were trying to synthesize all the different parts of who they are, rather than just erase the ill-fitting parts. Not just in terms of their background but in terms of their spirituality,” says Youssef.

When he booked an acting job at 20, his first goal was how could he use it to fill that gap that he saw, an intention that eventually manifested into the Ramy series.

Now that that gap has been filled, of course, the landscape has changed.

“The mere fact that Ramy exists has become a bit of a Bat Signal. Whether this show is for you or not, it’s a stake in the ground that has shown people that now that one is done, there is much more possibility for others to come,” says Youssef.

That is not just limited, of course, to his frequent collaborators like Amer, or director Chris Storer, who after helming a number of episodes in seasons 1 and 2 of Ramy, went on to create the phenomenon series The Bear. What Youssef is talking about is global, and he feels he’s barely scratched the surface with no time left to waste.

“I think the idea of ‘foreign’ film or TV—the label that anything outside of America gets saddled with—is over. I’m interested in going to Malaysia, to Dubai, to Saudi Arabia, and making a television show that is viewed with equal validity as a show that came from New York or L.A., with no caveats,” says Youssef.

A lot of that has to do with the way that streaming has changed how shows are positioned, with series like La Casa de Papel and Squid Game being watched without hesitation by anyone, anywhere in the world.

“When HBO made The Wire, a show intimately about Baltimore, they didn’t assume it was just for the people of Baltimore. That should be the same for a show made in Egypt. Make it with respect, make it with the people of Egypt in mind, but remember that it’s a human story, and people are going to dig it no matter where they are. That shift is already happening, and even Americans are watching things the way the rest of the world does, subtitles and all,” says Youssef.

“The infrastructure is being made available, but I don’t think that we are fully flexing the emotional nuance of it yet. I don’t like complaining about technology. I think it’s actually bringing us closer and creating great connections that weren’t there before. Now it’s just about how we calibrate that.”

That, then, is Youssef’s aim as he wraps up his first series—to travel the world and partner with the people that will tell the stories that will resonate everywhere, just as his series has resonated far beyond the borders of New Jersey. It’s a new chapter in his career, but it’s more than that. It’s a new chapter in his life.

I start to realize as Youssef excuses himself to the facilities that, much like the other times we’ve spoken at length, he doesn’t really spend that much time talking about himself. When we sat down, he got me chatting very quickly—“are you seeing anyone in Dubai?” he asked with a smile early on, leading to me oversharing and him enjoying every revelation—but the details he shares in return are scant.

In fact, the biggest revelation of our meal comes in an off-hand comment when I ask why he was eating egg whites. He had an upset stomach, he explained. He and his buddies had gone upstate for the weekend, and he’d caught a stomach bug—“but my wife didn’t get it, so yeah,” Youssef dropped.

I, at first, changed the subject, not realizing in that moment he’d just told me he’d recently gotten married, something he hadn’t yet announced. It turns out he is understandably over the moon about it, though he still wants to keep the details private, which I am happy to oblige.

But, given that it is my job, I have to prod him a little.

“Come on man, I’ve got to write a big glossy magazine cover profile on you. Your first ever! Tell me about your childhood traumas or whatever,” I demand as he sits back down.

“Alright, where should I start?” he says with a smirk.

Youssef starts with his father. His father, after all, set on a path a lot like his—a link that at first he struggles to articulate.

“I think a lot about how similar my and my dad’s journeys are. There’s something about a person who emigrates to America that’s very… hopeful. It’s spiritual. You don’t know what’s going to happen, and I felt that a lot stepping into a career where I’m constantly hoping to figure out how I can maintain my integrity as I continue to grow,” Youssef says.

Balancing the professional and personal hasn’t always been easy for Youssef.

It started when he first started doing sketch comedy in New York, begging people to watch his show, handing out flyer after flyer and asking friends to buy tickets just so the theatre would give them more dates.

“Everything can easily become about the work because all your friends are doing it too, and it all just becomes one big thing,” he explains.

The question then became about balance, the same lesson his father had always instilled in him as a kid, but because he’d already mixed it all up—friends and colleagues, ambition and fun, his personal and professional self—finding that balance became nearly impossible.

“I had this initial big push of ambition to just get something on the board, but even though I have, that impulse still hasn’t really gone away. In my mind, and in my body, I’m like, cool, now I’m just getting started. This genuinely still feels like the beginning. And as I get in the flow of actually doing all the things I want to do now, I have really had to focus on how to balance all the other parts of my life,” says Youssef.

Part of that has been about admitting to himself where he’s gone wrong, and giving himself fully to the things and people he’s neglected as he chased his ever multiplying dreams.

“I would say the last two years, versus the prior five years, I’m a way better friend. Even though I’ve gotten more busy, I got a time to assess that this is just as important. Once you achieve a little bit, you see that as cool as that is, being in great friendships, being in healthy relationships—as cheesy as it sounds, that stuff actually is worth more. But then you have to create a life where you can actually do that.”

“It’s like that LCD Soundsystem song, ‘All My Friends’,” I say. “Do you know that song?”

“No,” says Youssef.

“It goes, ‘You spent the first five years trying to get with the plan, and the next five years trying to be with your friends again,” I quote.

Youssef looks bowled over.

“Wow. That—it is that. That’s it,” he says.

It’s more than that, though. Because as the industry changes, it’s not just about separating your work self from your home self, and carving out a corner of compassion for your favourite few on the weekends—it’s about expanding that compassion to the work world, too.

Hollywood is changing. “I think this is part of a larger cultural shift in Hollywood. People want to be treated well. And I think there’s more opportunity, there’s more access, because people now know that they’re not untouchable.”

Youssef likes working in a Hollywood like that. He likes knowing that generally people are trying to be better people, and that he can approach the industry with the same heart that he can improving his own personal relationships.

Once again, his personal and professional goals can be in sync.

“None of this is fun if you feel like you’re becoming like a worse version of yourself,” he says.

“I feel like I’ve talked about this with you before,” he says, mentally scanning the years of conversations we’ve now had. “But the fantasizing I do about the lower selves of a lot of these characters is part of my ongoing fascination of the darkness that people can slip into in order to get what they want. That is a very direct form of self-therapizing that I’m doing.”

As we leave the diner and stroll out into the crisp air of New York’s late autumn, after a digression on how great Joaquin Phoenix’s wardrobe was in Her, I finally move the conversation on to all those future projects that he’s so excited about. First up there’s his next stand-up special, his first since 2019, that is heading to HBO.

Bigger than that is an animated comedy that is already well underway at Amazon that Youssef co-created with South Park alum Pam Brady. With Mona Chalabi, a journalist and illustrator, serving as executive producer, it is set in the early 2000s and explores bits and pieces from his life and comedy that he hasn’t had tapped into yet, all while taking in the absurdity and free-spirited perspectives of his collaborators.

“In terms of the next chapters, I’m really open to the wonder of that. Ten years ago I had a desire but I didn’t know what form it would take, now, the forms are a lot clearer, but I still don’t know how they’ll solidify,” says Youssef.

Part of that is being open to things that were never in his plan to begin with, such as the opportunity to star in a Yorgos Lanthimos film opposite Emma Stone, Willem Dafoe and Mark Ruffalo. No, seriously—it’s called Poor Things, and it’s coming out late in 2023.

“I’ve always had this immigrant mindset of, ‘alright, I’ll do as much as I can. I’ll catch what I can eat,’ But then suddenly this director I’m obsessed with just asked me to be in something he was making. That’s just a gift. How could you ever plan that? And it was truly one of the most creatively satisfying things I’ve ever been a part of, and all I had to do was show up,” says Youssef.

“That’s the thing, though. You can’t get to that without doing the stuff before.”

As Youssef repeats what a gift that was, there’s still some bashfulness in his delivery, as if a part of him still feels he should have used that time for something less him. But as Ramy comes to an end and he moves onto the next chapters of his life, a whole new generation of writers and producers—who had never had their voices heard before, coming from perspectives that had previously been shut out from the conversation— are already getting staffed or pitching their own series ideas. Even if he’s not actively shepherding, he’s opened more doors than he may realize.

This may still be the beginning, but there’s good reason to push past this part as quickly as possible. After all, once you move past the basics, the real fun begins.

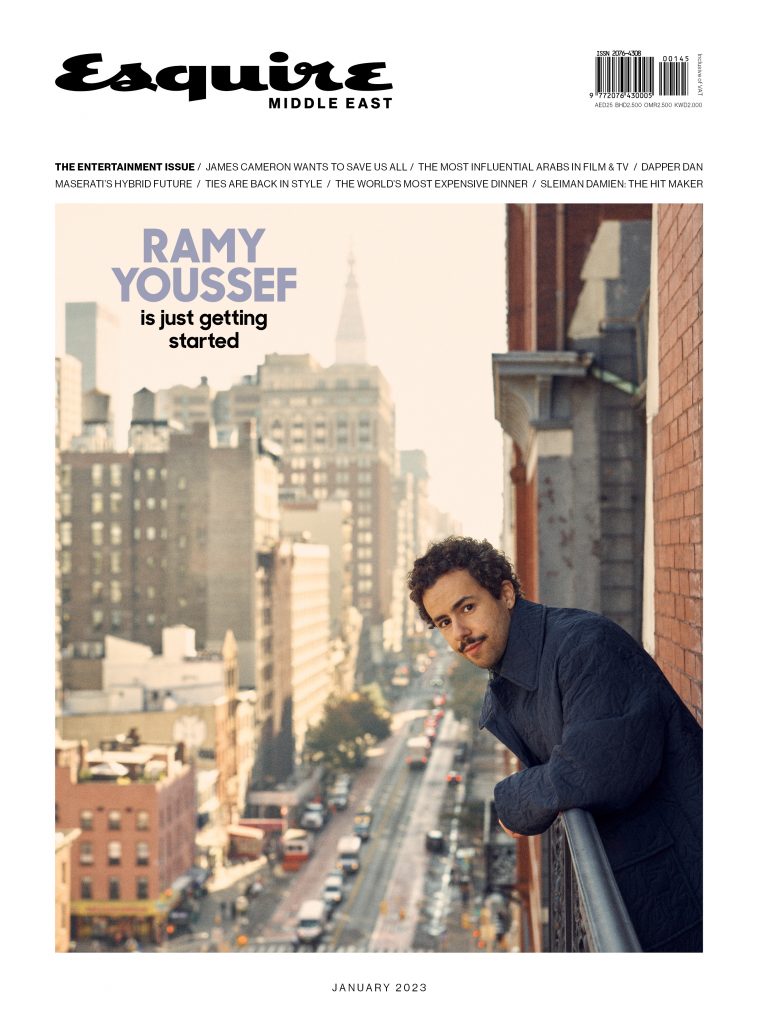

Photographer: Charlie Gray @Charliegraystudio

Styling: Laura Jane Brown @Laura.jane.brown

Producer: Steff Hawker @steffhawker

Hair by Andrea Grande-Capone

Makeup and grooming: Jennifer Brent @jennieredd with @traceymattinglyagency using Kiehl’s & Charlotte Tilbury

Read our full Ramy Youssef cover story in the January issue of Esquire Middle East, on newsstands now