If the question is: ‘How do you make cricket interesting to people that aren’t interested in cricket?’ The International Cricket Council’s answer is: Usain Bolt.

Last month, in Long Island, New York, an event was organised to help drive publicity ahead of the upcoming T20 Cricket World Cup. On that day it was overcast. A light, springtime shower was threatening to make an appearance, and aside from the occasional wry smile from the groundskeeper and nervous skywards glances from the organisers, the recently-finished Nassau County Cricket Stadium looked ready and fit for action.

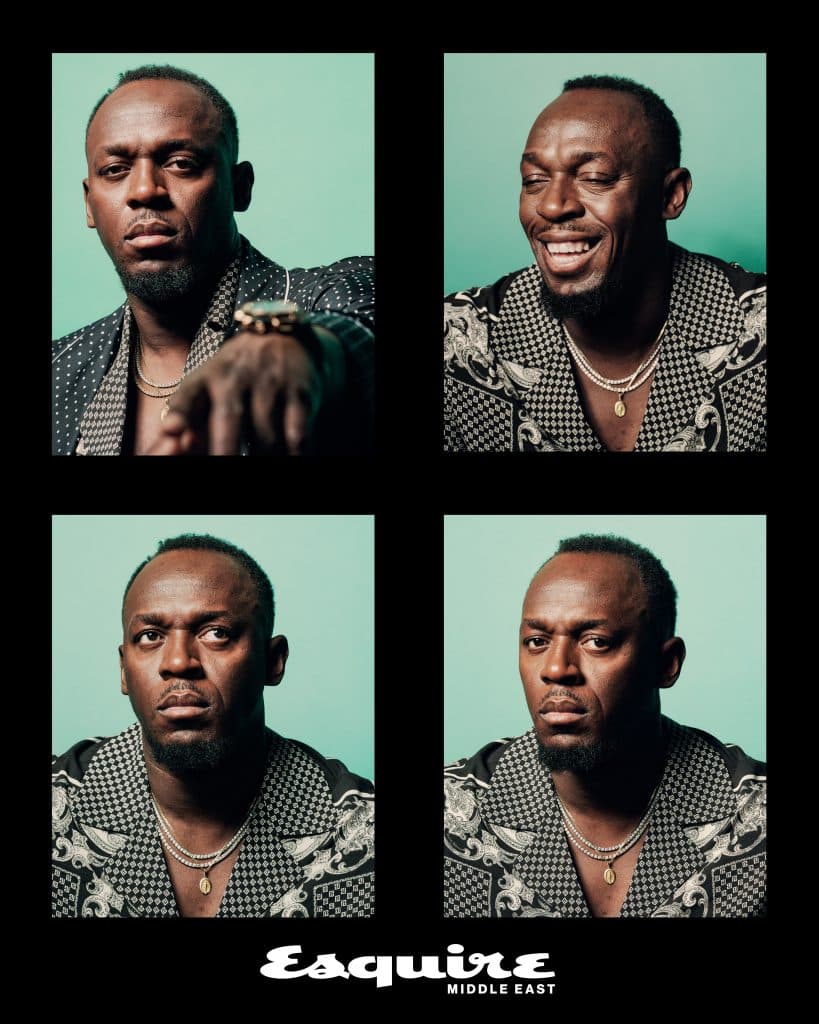

There was, however, one man showing total indifference to the weather—Usain Bolt. The Jamaican sprint king was striding about the lush, carpet-like green outfield with a cricket bat in his hands. His smile broad, his rangy 6’5” frame relaxed, and only the occasional flash of gold from the Hublot watch (worn under the ICC-branded purple cagoule) showed as he rolled his wrists pretending to hit cut shots to imaginary balls, separated him from the assembled crowd that were intentionally milling about.

The tournament that showcases cricket in its most explosive format is set to be held in June across the Caribbean and the US. But whereas Twenty-Twenty cricket guarantees star players hitting big and bowling fast, all to a backdrop of loud music, bright colours and a barrage of pyrotechnics—the concern is whether it is enough to peak the interest of the American sports fan.

Yes, that is correct, Usain Bolt is so well-known, and so ubiquitously loved, that other sports are now using the world’s greatest athlete to get people to take notice of them. That’s the kind of influence the fastest man who ever lived has—no need to Like, Follow, or Subscribe.

“You know, cricket was actually my first love,” Bolt admits on a call a few days later back at his house in Kingston, Jamaica. “I think it’s pretty cool that I get to be part of the sport now, because when I was younger, to be honest, I wasn’t really interested in track and field—I wanted to be a cricketer.” Bolt explains that despite (or maybe, because of) the popularity of cricket in the West Indies at the time, there was a lot of politics at play and it wasn’t always the case that the best players necessarily were selected to play.

“It was actually my dad who made the decision that I would commit to track and field once I went to high school. He was very savvy to the politics of Jamaican cricket at the time, and thought I would have a better chance of making a name for myself if I stuck to the track.”

That’s quite a wild statement to hear from the man who is not only widely regarded as one of the greatest track athletes ever, but who has the statistics to suggest that even that is an understatement.

When Bolt hung up his running spikes in 2017, he left the career as an eleven-time World Champion, with eight Olympic gold medals, three world records and enough other accolades to merit the trophy room that he is currently making the call from.

To put Bolt’s career achievements in another way, no other man has ever won both the 100m and 200m sprint events at two consecutive Olympic Games. Bolt did it at three. Therefore, if that record is to be challenged in the soonest time frame, someone will need to win both events in Paris this summer, and then not lose another Olympic race until 2032. Bolt is so successful that in the all-time Olympic medals table, if he himself was a country, he would be the 55th most successful country on that list. If we’re just talking about just the World Athletics Championships, he is 25th—winning more medals than every GCC country, combined.

To think that had his dad—Wellesley Bolt, a small shop owner in the town of Sherwood Content—not made the decision for his son to commit to track and field, the world may never have heard of Usain Bolt. Well, the cricket world might have.

It’s a hot day in Kingston. “Too hot,” according to Bolt who is sat in an air-conditioned room in his house. He’s wearing a basic yellow t-shirt, three thin gold chains around his neck and the relaxed demeanour of a man who is at ease in an interview. Behind him is a mounted black and white picture of him and his coach, Glen Mills, taken a while back at a local athletics track nearby. A humble reminder of the small details that helped build

a global superstar.

When he talks, he’s open, honest and charming—not trying to make jokes, but happy to laugh and respond at them if they are made. Our call has a timer on it. We’ve got about 40 minutes until his kids get home from school, and from there he passes the baton from global icon to dad.

Now 37, he has three children with his long-time girlfriend, Kasi Bennett. And if you thought that Usain St Leo Bolt had the name of someone who sounds like he was born to be fast, well he’s really stepped up the nominative determinism with his daughter Olympia Lightning (4), and twin boys, Thunder and Saint Leo (3). The plan is to chill for a bit, and maybe play a bit of backyard cricket later when the heat cools off. Bolt leans back in his chair, and stretches his arms, it’s hard to imagine that life ever gets him down—and, why would it? Things in the Bolt household tend to go entirely to plan.

“I wanted to have three kids, so having twins helped,” he says. “I’m also glad that they are so close in age, it means that they’ll all be off to college at the same time, and I can get my life back!” he says with a smile.

Do your kids understand who their dad is? I ask.

“Not really. I’ve spoke to other athletes about this and what I’ve noticed with kids is that no matter how good or successful a sports person their parents are, they just don’t look up to you that way,” he laughs. “Hopefully by the time that my kids are old enough to properly understand track and field, I will still have my world records, and so they will have to put some respect on my name!”

Bolt set both the 100m (9.58 seconds) and 200m (19.19 seconds) world records in the glorious summer of 2009. A year after he exploded into the global consciousness with his then-record-setting performances at the Olympics in Beijing, he scorched the competition at the World Athletics Championships in Berlin running both distances faster than they had ever been run before, or since. Fifteen years on, do the records still matter to him?

“They are still a big deal to me,” he admits. “I think the longer that it goes on, the better it feels. Especially now that I am retired, they help keep me relevant in the sport, and that means a lot to me.”

So far, there has been a lot of hyperbole about Usain Bolt’s career exploits in this article. It’s hard not to—there are many. But medals and records aside, part of what catapulted the Jamaican into superstardom was, well, who he is. On the TV, Bolt comes across as immensely likeable, grinning from ear-to-ear and always ready to burst into song and dance, throwing up his now-famous ‘to di world’ lightning bolt pose. He’s an entertainer, and he likes being one.

During his career, there was an on-going criticism that his demeanour (and his dancing) were signs that he didn’t take running seriously enough. There’s a perception in some quarters of the athletic community that Usain Bolt was the Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart of track and field—a prodigiously gifted individual who is also something of a wastrel and clown. Certain people, when they see a man perform superhuman feats, want that man to carry himself with superhuman gravity. Bolt, by this measure, never fails to disappoint.

“Yes, people showed up to watch me run fast, but I believe that it was the fun side of me—the cool side of me—is what people came back for, what they gravitated to,” he says. “I was never there to show up, run and leave—that’s not who I am. I’m there to have a good time.”

I can confirm, on the several occasions when I have met him over the years, he is every bit as genuine as he is on-screen. Open, warm, and happy to talk about pretty much anything.

Does he ever lose his cool with being the centre of attention wherever he goes? “You know, I always say, if you’re famous and you’re in a bad mood, then just stay home that day. Unfortunately, people love it when celebrities do something bad, so the way I see it, is if I’m not in a good mood, and I don’t want people to ask me for pictures, then I’ll just stay at home and avoid the drama.”

How often does someone challenge you to a race? I ask.

“Oh man, pretty much every day!” he chuckles. “It’s probably the thing I get asked the most, but the thing is, they don’t really want to race me! Not even Asafa Powell or Tyson Gay wanted to race me!”

It’s true. When it came to the on-track performance, Bolt was not just one step ahead of the rest, but three. When he set the current 100m record in Berlin, it took him forty-one steps to reach the finish line. In second place, Gay needed forty-four steps to cover the same distance. So the simplest—and most literal—explanation for Bolt’s speed was that he cycled his stride nearly as quickly as other sprinters, but because of his longer legs, his stride length was greater than theirs. Or to put it in another way, he’s a tall man who ran like a shorter one.

“People would always think ‘he’s Usain Bolt, of course he’s always in front’ but he had his demons that he dealt with as well,” the former men’s 110m Hurdles record holder, Colin Jackson once told Athletics Weekly. Jackson is a close friend of Bolt, and has often said that the biggest misconception of the Jamaican star was that he didn’t care about athletics. According to Jackson, that couldn’t be further from the truth. “He knows his sport inside out—he’s an athletics connoisseur, and that is really important,” said Jackson. “We paint the picture of him being this iconic figure that is untouchable but in reality he is a normal guy blessed with incredible height and skill—and he applied it so well.”

The simple truth of the Usain Bolt that we’ve seen smiling and strutting away on the startline, was that when it was finally time to race he knew that by that point, there was nothing more he could do—so he just tried to enjoy the moment.

“I never worried when I got to the starting line,” he explains. “By that point, I’d either have prepared enough to win the race, or I hadn’t. All the hard work comes in the training for six to eight months before.” Perhaps that was the secret to why Bolt always looked so relaxed and was almost playful moments before the start of his races. When the eyes of the world are on him; when elite athletes to his right and left had the sole intention of beating him; when the spotlight was at its very brightest—he was completely calm in the knowledge that he had put in the work.

“My coach used to talk to me about muscle memory,” says Bolt. “If you do the same thing over and over again, your body just instinctively knows what to do when the time comes. All the repetition in training is about making sure your mind and muscles are in tune, and once they are, they will figure out ways to make it easier for you.”

It’s a telling choice of words, ‘making it easier’, as that is how the world described a lot of Bolt’s most iconic moments. Him easing up, arms beating his chest celebrating even before crossing the finish line in Beijing; him smiling at Canadian sprinter Andre De Grasse as he dared try to beat him to the line in the semi-final in Rio de Janeiro. “That was one of my worst traits,” admits Bolt about the fact that he would often watch the other competitors while running. “My coach hated it! But I just couldn’t stop it. I would always look around to see where I was, to see if I was going to win, or if I needed to work harder.” For revisionist historians, the question of ‘what if Bolt had not eased up in Beijing?’ still lingers. But does Bolt feel the same? Could he have shaved even more time off of the world record if he had run ‘through the line’ as his coach had asked?

“No,” he puts flatly. “My dream was to win an Olympic gold, and that was my first. I already had the world record, so I wasn’t even thinking about it. I was just thinking ‘oh my god, I’m going to win!’ and I wanted to be in the moment. That one was for me, and for everything I had worked towards. Could I have run faster? Maybe, but honestly, I don’t care.”

As Jackson suggested, Bolt’s commitment to competing (and winning) in track and field was never in doubt.

Despite no longer racing, Usain Bolt will be set to make another first at this summer’s Olympics in Paris—the first time he has attended the Games as a spectator.

“I’ve never watched a Championships before as a fan!” he says with a chuckle. “Because I would run three events [100m, 200m and 4x100m relay], I would be competing all throughout the Championships, so I never actually get to go to the stadium to watch the races or experience the atmosphere as a fan. It’s kind of crazy when you think about it.” Crazy seems an apt term. It does seem a little crazy that a man whose very name is synonymous with so much Olympic legacy—having done things that literally no one else ever has, and yet, he has not done the one thing that hundreds of thousands of others have, and potentially the most important aspect of it all: sit in the crowd and cheer.

“I’m really looking forward to it. Obviously, I want to watch the 100m and 200m—the 200m being my favourite event, of course.” When asked who he has his eye on, while he does ear-mark US sprinter Noah Lyles as the favourite for the 200m, the 100m title he sees as much more wide open. “No one has really run that fast this year, so it is really there for the taking, like it was last time [with Italy’s Marcel Jacobs unexpectedly winning in Tokyo 2020]. But it will start to become clearer who the contenders are towards the end of June, as we get closer.” Outside of athletics, Bolt is keen on watching other sports including the swimming, basketball and maybe even a classic Olympic event like beach volleyball.

“Hopefully, I’ll have the time,” he says. “I’m bringing the kids with me. They are still young, but hopefully they will remember something from it.”

Speaking of his kids, Bolt checks his watch, it’s one that I’ve been eyeing up throughout the conversation. It’s kind of hard not to. The chunky 45mm yellow gold Big Bang Unico strapped to his wrist was made for him by Hublot—one of the benefits of his long-term partnership as a Brand Ambassador with the high-end Swiss watchmaker.

“Gold looks good on you,” I quip.

“I agree,” he replies deadpan.

Over his career, loyalty has been one of the most underrated personality traits of Usain Bolt. Alongside a partnership with Hublot which started back in 2010, he has also shown unwavering commitment to his other major sponsor Puma—who he has been with since he was 16 years old—and to other members of his team, including his coach, his agent, and his best friend (and manager), ‘NJ’, who he has known since first grade.

“Loyalty is very important to me, because it’s hard to find it in the world,” he says. “When you find a person, or a brand, that you mesh with and you share the same goals and values, you need to nurture it. Life isn’t about making a fast buck, it is about building something from the ground up. Most of the people around me have been with me since long before I was anybody, and that means a lot. If I feel that you want the best for me, then I will give that back to you.” He credits that mindset to his parents, who he says “raised [him] right” by always showing him the importance of being a good person. He’s adamant that it is something that he plans on passing on to his kids—whether they realise he’s famous or not.

“The funny thing is, these days my parents say to me: ‘Usain, stop giving away all your money!’” he laughs. “I’m, like, you can’t cuss me for being nice to people, I learned that from you!”

What we can gather from an Usain Bolt who has neatly transitioned into life as a retired star, is that even though he is no longer competing, he is still using the lessons that he picked up over his career to benefit others. Those who rely on him, those who are loyal to him, and those who share his passions and set of values. Life may look simple for the fastest man on earth, but he has put the work in to get himself to this point. But, right now, he’s off to play some cricket.

Photography by Simon Emmett / Styling by Tanja Martin / Grooming by Michael Richmond with ME Agency / Tailoring by Holly Pitt Knowles / Styling Assitance by Sonia Jermyn / Digi Tech by Sam Ford / Lighting Assistance by Guy Parsonage / Production by Tilly Pearson / Senior Producer: Steff Hawker / Special thanks to: Kimpton Clocktower Hotel