“Heeeeeeyyyyy Ramsay Short!”

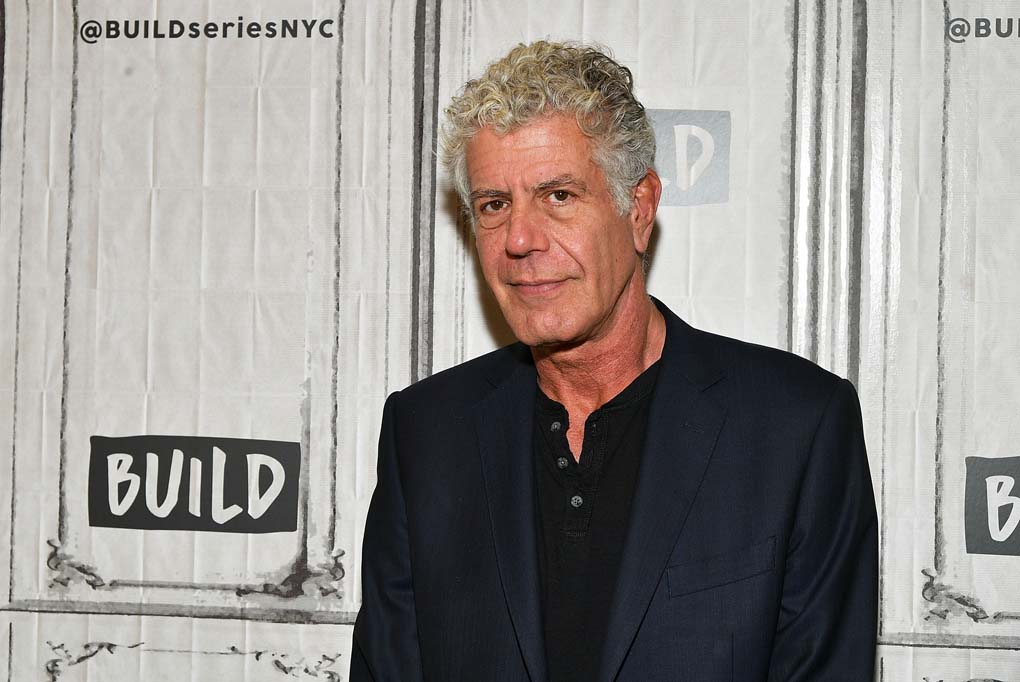

Anthony Bourdain would always greet me the same way. His booming New York twang would annunciate every syllable as he pulled me into a bear hug. He was a lot taller than me, and an expert in Brazilian Jujitsu so his bear hugs were always an experience. I shall miss them. As I shall miss him.

Along with hundreds of thousands of his television viewers, friends, individuals and people of countries all around the world who knew him or watched his prolific shows.

For them he was that unique sort of advocate, a man blessed with unflinching honesty, great humanity, deep political conviction, caustic wit and an ability to show—often by simply listening—how ‘other’ people weren’t all that different from ourselves.

****

he first time I met Tony—as he preferred to be called—I had no idea who he was.

It was summer in 2006, and I was a journalist living in Beirut as a correspondent for The Daily Telegraph newspaper. I was into food, but not food programmes.

I took a call from a TV producer friend working for No Reservations, Bourdain’s show on The Travel Channel, asking if I wanted to take some American chef out to experience Beirut’s celebrated nightlife and street food. “Of course,” I said. “When? Saturday night? The twelfth? Sky Bar? No problem.”

I vaguely remembered that this ‘celeb-chef’ had written a tell-all memoir called Kitchen Confidential that had caused a stir when it came out a few years earlier, but that was about it. I supposed I should have looked the guy up, but just didn’t get round to it. To be honest, I was a little dismissive. Why is an American coming here? What new lies or clichés is he going to spout about Beirut this time?

The twelfth came, and at the entrance to Sky Bar—the hippest of Beirut’s rooftop clubs—I met a tall, slightly awkward guy, in a blazer and jeans, who came across as a little shy. We drank with some glamorous female friends and talked as the music blared.

Tony was awe-struck by it all, he had no idea how open and progressive everyone was. For him, like most of his American viewers, Beirut was a den of terrorists, a war-torn Islamic state, it was the US Embassy bombing of 1983, and it was the danger zone of Hollywood action movies where all the bad guys with atrocious accents came from. Could it really be, well…this?

From there we went to a late night shawarma joint named Barbar in Hamra. In the cab on the way we clicked, and were friends ever since. He wanted to know everything, about Beirut, about me.

We talked music (one of his great loves), about grandmothers (mine was a wonderful Lebanese matriarch for whom cooking and eating and conversation was, as Lebanese and Arabs know well, what life was all about). And we talked Lebanese food.

At Barbar we ordered kebabs, started filming, and spoke about the Lebanese people, the complex history and what it was like for me documenting this eclectic, crazy, cultured and edgy city – topics we’d return to constantly for the next decade.

And then the news filtered through….

Calls from the Telegraph’s foreign desk on the line from London – the airport had just been bombed a couple of miles away from where we were sitting. I knew that life as we knew it in Beirut was over.

We wrapped the shoot. Tony and his crew moved out quickly on orders of a local CIA agent and spent the next few weeks holed up in a hotel outside the city in a ‘safe’ area watching bombs drop like a grotesque firework display, until the US marines were able to evacuate them.

It marked him.

I spent the next 34 days, sleepless, reporting from bombsites, the south, seeing the horror of war and death first hand, on the front line and even spending six hours being kidnapped and beaten by a local militia.

Throughout the war Tony and I spoke on the phone, he was keen to get my take on what was happening, to understand the complexities of the conflict as well as the complexities of the Lebanese people.

He couldn’t make the programme he had wanted to make initially – it’s amazing he made any programme at all – but the show that did air was nominated for an Emmy award and became one of his most watched episodes.

What was telling was that it never became about him. It was always about Lebanon, his concern for the country and the people, and what was happening, a city and people even in this short time he had grown to love.

****

This was what Tony did. Firstly with his programmes on The Travel Channel and later with Parts Unknown on CNN.

They were both incredibly honest portraits of people and their circumstances, exactly as he saw it. No bias, no bullshit.

Tony was not a man who would take any crap — if he thought you were talking nonsense he would call you on it. This was something that endeared his viewers to him, endeared him to me, and was what made him an excellent journalist and storyteller.

I later devoured Kitchen Confidential.

“When you’ve seen what I’ve seen on a regular basis it changes your world view. I’ve spent such a lot of time in the developing world. I was caught in a war in Beirut, been in Liberia, the Congo, Iraq and Libya and realised how fast things can get bad, how arbitrary good fortune and cruelty and death. I suppose I’ve learnt humility. Or something,” he told The Guardian last year.

He certainly had.

As the years passed after 2006, we kept in touch and met up fleetingly if I was passing through New York or he was passing through London, where I’d decamped to after my daughter was born that same year.

Tony also had a daughter in 2007 (“Flew home from Beirut, my wife was there. We went right home, and made a baby. That was the day that my daughter was conceived,”) and fatherhood was something we shared, a bond that tied us, both children conceived in difficult times. We’d always relate tales of the girls and how being dads changed our perspectives on the world.

Being a father was something he adored. This fact, and the fact of what he witnessed in Beirut in 2006, changed the way he made his shows. Whereas before things had been less serious, now as he travelled to Cuba and Haiti and Iraq and Liberia, he increasingly used conversations based around food to tell the stories and indeed the politics of the places he visited.

He understood like my grandmother that eating and talking about food brought people’s guards down, and open, fruitful discussions ensued. And how it worked. What success it brought him and what brilliant shows he made.

We both returned to Beirut in 2010 to make the more light-hearted show he’d originally intended to make in the first place. With the customary barehug and a “Heeeeeeyyyyy Ramsay Short!” we set off to film two pals drinking on the beaches of Batroun and putting the world to rights.

Munching falafel from the feuding brothers Sayhoun, eating baby sparrows at Armenian restaurant Onno (“Oh, they’re cute. It’s the crunchy heads that make them good,” he quipped), sampling wine and arak at Massaya in the Bekaa, eating incredible sfiha in Baalbek and touring the Roman temples.

We spent a night eating incredible fish and shellfish at Chez Maggie’s, a beachside shack also in Batroun where the loud and sarcastic Maggie was immediately enamoured with Tony, a scene that didn’t make the final cut. And everywhere we went this unassuming man with an almost a childish glee for everything he did and saw embraced the people he met and was in turn embraced by them.

He summed up Beirut, and indeed Lebanon best in a 2014 interview with Blogs of War: “The food’s delicious, the people are awesome. It’s a party town. And everything wrong with the world is there.

Hopefully, you will come back smarter about the world. You’ll understand a little more about how uninformed people are when they talk about that part of the world. You’ll come back as I did: changed and cautiously hopeful and confused in the best possible way.”

Unlike so many others he got it. He got Beirut, and the Arab world. He knew there was so much more. We respected him, the people of Lebanon, Iraq, Gaza (on the latter he said, “The world has visited many terrible things on the Palestinian people, none more shameful than robbing them of their basic humanity,”) as someone who simply portrayed and understood that we were all ordinary people trying to live our lives all experiencing the same human emotions and struggles everyone felt in the West.

It was so much more relatable than hard news documentaries.

****

In 2015, he returned to Beirut for, sadly, the last time.

I hooked him up with Lebanon’s Harley Davidson riders, and we went biking around the city. Later at Abu Elie’s hole-in-the-wall Communist-themed bar where Abu Elie’s son, the DJ and Arabic vinyl collector Ernesto Chahoud, hosted us.

That night, a night that could have happened in any crazy bar anywhere in the world, was a moment that will stay with me.

As the drinks flow so does the conversation: from the bar’s décor of socialist flags, images of Communist Arab leaders and posters of Che Guevara to Beirut’s construction boom and the Syrian crisis just 140km away on the eastern border.

“So what’s with the ammunition on the walls?” Tony asks Chahoud.

“Hah! Those are from the Civil War [1975-1990]. My dad used to fight for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and when he stopped and opened the bar he kept some bullets,” replies Chadhoud.

“But that’s nothing, you should look at this,” he continues, ducking down behind the bar. Pulling out a Swedish-made, Egyptian Port Said submachine gun. “Check this out, this is an original.”

He thrusts it into Tony’s scarred hands. The film crew get a little twitchy. Tony takes the gun and Chadhoud points out the magazine and bolt-mechanism. In our inebriated state we look over it bemused while the film crew in the corner are manically whispering, “He’s getting out the gun, he’s getting out the gun. Don’t panic!”

Tony plays it cool. He’s been in far more trying situations than this on his travels and clearly realises there’s no danger. The gun is at least 50 years old, rusting and looks more like a prop from an Indiana Jones movie than a functioning firearm.

Chadhoud removes the gun, and we raise our glasses of shouting “Kesak,” [Lebanese Arabic for ‘cheers’]. The film crew visibly relaxes.

Just another night in Beirut. It made for some excellent TV.

****

The news of him taking his life last month in France hit me hard. Very hard.

Still raw as I write this, I grieve deeply for Tony and his family, trying to imagine the mental strain he was under which pushed him over the edge. But I find solace in remembered the man I first met outside of Sky Bar more than a decade ago.

That tall, slightly awkward guy, in a blazer and jeans. The guy who was shy off screen, slightly vulnerable and passionately creative. He was someone who’s early life and later travels had given him a deeper understanding of people and places intuitively.

A man who understood exactly what Mark Twain was referring to when he wrote: “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.”

For those unable to travel, his TV programmes brought the outside world to places they could only dream of visiting, and he did it with an empathy the rest of us could sorely do with today.

Kesak, Tony.