The popular western conception of a camel is that it is a lousy, ill-tempered creature that would sooner swim the Nile backstroke than run a race. Disney’s Aladdin can shoulder some of this blame, as should the hype men and women of the camel’s wealthier equestrian rival. Because here’s what Big Horse doesn’t want you to know: camel racing is way better than horse racing, and it’s not even close. Horses are musclebound bores and bimbos, gym influencers, and they run as workaday as air conditioners. Horses are post-2004 Coldplay. They are Priuses.

A camel is tough and juiced like a stock car, with the durability of a tank. It will plod gamely for days through deserts on a thimbleful of water. But at full-tilt it will thunder like a Catherine wheel, on legs that bend and fall like wet spaghetti—if it wants to. Camels are unwieldy, sometimes unwilling runners, as irritable as truck drivers on a double shift. You never quite know what you’ll get, and riders’ tactics are often boiled down to: hold on, and pray. But perfection is not a synonym for fun, and a camel race is a thing of unbridled, insane, joy. Nobody at Mexico’s Azteca stadium in 1986 had their eyes on Lothar Matthäus when Diego Maradona was on the ball, and nobody watches Priuses go at it when the demolition derby comes to town.

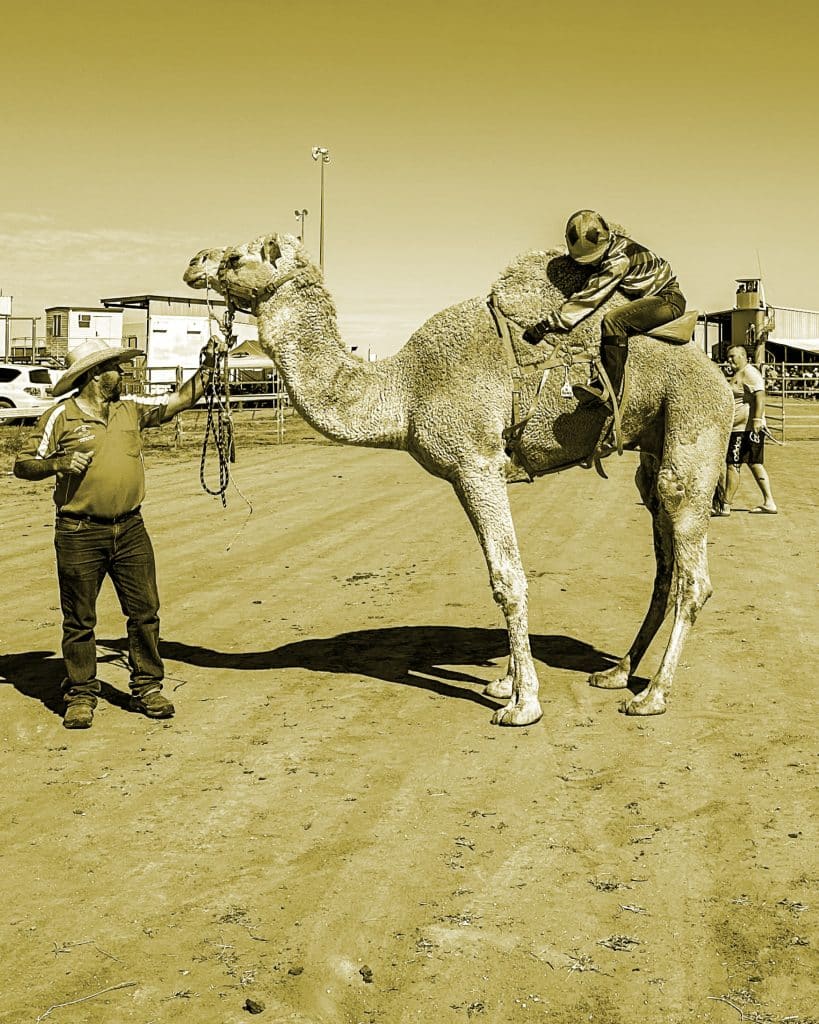

That thought—okay, a briefer version of it—hit me about half a second into the opening heat of this year’s Boulia Camel Races, a madcap, three-day festival held each July in the heart of the Australian Outback. By that time one of eight starters had chewed its handler’s arm, another had thrown down its rider and bolted for the finish line, and another two had defied sense by darting sideways toward the guardrail. Boulia is Australia’s richest camel tournament, and organizers call it “The Melbourne Cup of Camel Racing” in reference to the country’s richest and best-known Thoroughbred stakes. But slapstick is just one of a myriad differences between the two events (as far as I know, Melbourne doesn’t kick off with a fancy-dress lawnmower race). Another is money: Boulia’s total prize pot is $45,000; Melbourne’s is $14 million. And there is Boulia itself, population 314, a farm town only slightly more accessible than Narnia, where the dirt is red and camels roam on stations larger than many sovereign states.

It is 600 miles from Townsville, on the Queensland coast, to Boulia, close to the border with Northern Territory, and I had spent two days driving that route with the man who founded the races 27 years ago. Paddy McHugh is Mr Camel in these parts, as synonymous with the beast as Jim Henson is to woolen frogs. Family tragedy introduced McHugh to the camel half a century ago, and he tamed it along one of the craziest endurance races ever attempted by man. Since then he has owed camels, a life of extraordinary adventure that has seen him, among many, many other things, party with Gaddafi’s toughs in Tripoli, traipse the Mongolian desert, and feast with the glitzy movers and shakers in the Arabian Gulf, where the wealth of the camel races eclipse even the Melbourne Cup.

“The prospect of a global camel racing circuit is mouthwatering—but so is world peace. Formula One began in 1950 when a clique of wealthy European race organisers joined together, could camel racing do the same?”

But McHugh is no conservationist. Australia’s million-plus dromedaries—two-humpers—are the only wild flock on earth, and they’re widely considered pests. Rather than cull them, which Aussie roughnecks do with rifles from the skids of lightweight helicopters, McHugh wants to turn them into a multinational meat and milk industry. He is sure it is worth billions. The dynamite that will blow open this klondike is an even grander, more improbable vision: a global camel racing tournament, plotting the world’s disparate camel nations along a single, Formula One-style season.

It is why he returned to Boulia with me after over half a decade away, in a year the UN has designated its ‘International Year of the Camelid’. And it is why, as a mud-brown bull romped home to win that opening, quarter-mile dash, he was stood a few yards from the finishing post, his pale skin reddening in the morning sun, telling me and anybody who’d listen that Boulia could be the Yas Island of a brave new sporting franchise in the vein of LIV Golf, or the Saudi Pro League. Now aged 66, he says he has practiced some version of this pitch with over a thousand people, in five-dozen countries. The maddest thing isn’t that he still believes it. It’s that he might just pull it off.

McHugh describes his journey into the camel world as predestined. But it was not. He was born in Hughenden, which is seven hours from Boulia, and whose population of 1,113 hasn’t much changed since he was born there, in 1957. The family had scrabbled a level of comfort after years living in sheds with dirt floors, but in 1964 McHugh’s father, a Second World War veteran who drank and smoked heavily, got caught up in a bad sheep deal and moved them to Townsville. McHugh, short and toothpick thin, grew to despise the teachers at his new Catholic school, who strapped and slapped children into obeisance, gave up on becoming a priest himself, and lost his faith altogether after watching an episode of Star Trek.

McHugh’s father died not long after, from emphysema. From then on, McHugh’s adolescence assumed the Houdini act of so many young boys, getting into trouble at school and escaping into the bush to shoot kangaroos, or emus, or rabbits, or anything else that moved and tasted good. Aged 17 he performed his first skydive, and nothing else mattered any more. Any money he got on plumbing or roofing jobs went straight into the sport: McHugh became Australia’s youngest skydive instructor, and he jumped for Australia’s national team.

But the Outback came calling, or rather, it called McHugh’s older brother Greg, who hitchhiked over a thousand miles from Townsville to Alice Springs, near Australia’s dead-centre, in search of a donkey. En route, a trucker told Greg a little-known fact: that Australia’s interior was home to over a million wild dromedary camels. When Greg returned weeks later, the full story he and McHugh researched was even more remarkable. In the 1830s, white colonists had struggled to navigate the Bush on horses that spooked easily, and tired often. They imported Australia’s first camel, Harry, in 1840, alongside thousands of cameleers, whom they called “Afghans” but who also came from modern-day Pakistan, India, and as far away as Turkey and Egypt. In 1851 a prospector named Edward Hargreaves claimed to have discovered gold in a village called Orange, between Sydney and Melbourne, prompting a gold rush so big that for a short time, Melbourne was the second-most-populous city in the British Empire—ahead of Bombay, Lagos and Hong Kong.

Afghan-led caravans powered the gold rush, and camels became a lucrative business in their own right: between 1870 and 1900 over 2,000 Afghans and 15,000 camels arrived in Australia. The cameleers even built the region’s first mosque in a hamlet around 500 miles south of Alice Springs, on the edge of the vast Simpson Desert. Sixteen camels had travelled on the most famous journey of them all, in 1860, when Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills led a team almost 2,000 miles from Melbourne north to the Gulf of Carpentaria, in Queensland, passing close by what two decades later would become Boulia (the expedition is a cornerstone of colonial Australian lore, inspiring dozens of books and a 1985 blockbuster movie). “They say Australia was built on the back of the sheep,” one camel trainer told me in Boulia. “I reckon it was the camel.”

Greg returned from Alice Springs, and the brothers set out on their first camel trek, covering 600-or-so miles in a little under two months. It was the longest McHugh had spent without a skydive, and he was hooked. But Greg developed leukemia, and his health quickly worsened. McHugh donated Greg marrow from his spine, which in 1976 meant an injection with a syringe the size of a lightsaber. Doctors warned him the procedure would have psychological effects, and he suffered almost constant nightmares. Months later a sore on Greg’s mouth got an infection which squirmed its way inside his body. McHugh watched him die. Like most countryfolk he’s not much given to expressions of grief, and describes this moment as, merely, “fascinating.”

Greg left McHugh a 350-acre property in the gold-rush town of Gulgong, near Orange, and some camels. But he was in no mood to stop escaping, and hatched a plan to retrace the Burke and Wills on camelback. He had learned how to muster the creatures with a lasso while strapped to the bullbar of a four-by-four, and set out with a group of Aboriginal people and a zoo vet from Sydney. But around 1,000 miles in, somewhere in rural Queensland, the vet got into a bar fight and flew home, leaving McHugh and the others with the camels and ten dollars in cash. It took them four months to divert to Townsville and drop the flock there. It was his “major awakening,” he told me. “I had no experience. And I learned the hard way, I really did.”

McHugh never stopped having the nightmares this entire time. He blamed Gulgong, donated all 350 acres to the New South Wales Parks and Wildlife Services, and headed back out to skydive, developing a rangefinder camera special-made to capture dives. McHugh dove into music festivals, cup finals—anywhere. By the age of 30 he had jumped around 3,500 times, he thinks, and he was a director of the Australian Parachute Federation. He got married, and had three children, and lived in Townsville. He occasionally mustered camels. But they weren’t much on his mind until 1988, when a billionaire property tycoon decided to commemorate the bicentennial of European settlement in Australia by conceiving a 2,011-mile race from Uluru, then widely known by its colonial name, Ayer’s Rock, to the Gold Coast, in Queensland, which was hosting that year’s World Expo (Aboriginal Australians had, of course, migrated to the continent some 65,000 years earlier). Sixty-nine teams applied to compete for a $45,000 winner’s prize (around $122,000 today).

It would be the longest animal endurance race in history, and it would be contested on the backs of—what else—camels. Trains and motor vehicles had rendered Australia’s camel industry obsolete by the 1930s, and many of the Afghans returned home. But they released their camels into the wild and, with no natural predators and a habitat as perfect as the Sahara, a few thousand camels quickly turned into hundreds of thousands. Camels were the backbone of the Outback’s economy. But they were also a menace, destroying vegetation and sucking waterholes dry. The camel’s “only natural enemy is man,” wrote Robyn Davidson in her 1980 book Tracks, and some farmers attempted to cull its numbers by massacring herds from helicopters. But in Australia’s near-million square miles of desert, it was a lost cause. “Camels are almost uniquely brilliant at surviving the conditions in the Outback,” says British explorer Simon Reeve. “Introducing them was short-term genius and long-term disaster.”

“In camel racing, you stick to the simple maxim: “A slow camel’s a slow camel and a fast one’s a fast one.”

It would be the longest animal endurance race in history, and it would be contested on the backs of—what else—camels. Trains and motor vehicles had rendered Australia’s camel industry obsolete by the 1930s, and many of the Afghans returned home. But they released their camels into the wild and, with no natural predators and a habitat as perfect as the Sahara, a few thousand camels quickly turned into hundreds of thousands. Camels were the backbone of the Outback’s economy. But they were also a menace, destroying vegetation and sucking waterholes dry.

The camel’s “only natural enemy is man,” wrote Robyn Davidson in her 1980 book Tracks, and some farmers attempted to cull its numbers by massacring herds from helicopters. But in Australia’s near-million square miles of desert, it was a lost cause. “Camels are almost uniquely brilliant at surviving the conditions in the Outback,” says British explorer Simon Reeve. “Introducing them was short-term genius and long-term disaster.”

The Great Australian Camel Race, therefore, might not only celebrate the Outback but its chosen beast of burden, educating Australians about one of the least-known pillars of their modern history. Over a decade after Greg’s death and the disastrous Burke and Wills tour, McHugh decided to compete. Still rake thin, with a shaggy beard and halo of wild, brown hair, and dressed in undershirts and wide-brimmed hats, he looked like a sunstroke vision of a gold-rush pan-handler. His setup was old-hat too, compared to some of the competition, which included a team of ex-marathon runners and two Australian military troops; one from its famed special forces.

By comparison, McHugh’s entourage included a TV crew, his wife Virginia and one-year-old daughter. But he had a plan. He would break in his camels as close to the race as possible, believing they’d grow idle if left in a paddock. And he walked them for hours each day along the beach, hoping the sand would build their muscles. Leg one was a 255-mile journey from Uluru to Alice Springs. McHugh finished well. But organisers erected the racers’ camp beside the town’s sewage works, and almost the entire field was struck down by a form of dysentery, including McHugh’s daughter, who also contracted chickenpox.

Nineteen teams dropped out before leg two, a 473-mile slog north to Boulia, and dozens more succumbed to heat, exhaustion and their camels’ reactions to the huge, articulated “road-trains” that thundered along Queensland’s remote highways. Only 24 teams made it to Gold Coast, where a New Zealand-born carpet fitter named Gordon O’Connell beat the Special Forces team, some of whose men had lost 12 kilos, by 30 hours.

McHugh’s daughter recovered, and he placed ninth, blaming in part his commitment to the TV crew. But the experience had opened his eyes to a new kind of self-promotion, and reignited his passion for camels. The family moved to the surf town of Byron Bay, trading camels and selling rides along the beach. “I was full-on into camels,” he told me. Crucially, the 1988 race had also caught the eye of Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, ruler of Abu Dhabi, who contacted McHugh about opening an Australian camel-export office.

McHugh wrangled around a thousand camels, which the Sheikh whittled down to a couple dozen, which McHugh then trucked over 600 miles to Darwin, on Australia’s northern edge, and packed them onto an Airbus 340 in the dead of night to avoid media attention. To the Emiratis, it seemed money was no object, and they soon invited McHugh to the palaces of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, where he discussed camels with some of the region’s most important people.

Before long, McHugh had become Australia’s unofficial camel emissary, hopping on long hauls to parts of the world he’d barely considered as a boy in Townsville. It would bring him circling back, strangely enough, to Boulia, the tiny place he’d visited on the race—and the springboard for what he hopes will be his ultimate legacy.

Because camels are so closely associated with the Middle East and North Africa, you might assume they originated there. You’d be wrong. Camelids, which include llamas, alpacas, vicuñas and guanacos, actually evolved in North America around 40 million years ago, and they once included Titanotylopus, the largest camelid that has ever lived, which stood 3.5 metres high at the shoulder and roamed through what is now Texas, Kansas, Nebraska and Arizona. Paracamelus, the modern camel’s closest ancestor, crossed the Bering Strait six or seven million years ago, after which dromedaries settled west in Arabia and the Sahara, and Bactrian camels, which have a single hump, on the frozen Eurasian steppes.

For millennia camels connected the great civilisations of antiquity: in the 5th century BC, the Greek historian Herodotus described a caravan that stretched from the Egyptian city of Thebes over 1,500 miles to Niger, and Romans used them to the extent that archaeologists have discovered camel remains in London’s Greenwich Park.

Camel racing can be traced back to at least the 7th century, on the Arabian Peninsula, around the same time as the emergence of Islam: the Quran mentions camels over a dozen times, and it is listed by Allah as an example of the beauty of his creation. And while there is camel racing wherever in the world there are camels, from Morocco to Mongolia, the Gulf is still the sport’s undisputed king.

Taif, near Mecca, each year hosts the Crown Prince Camel Festival, the largest and richest event on earth, with over 11,000 camels and an $18m prize pot. Races stretch between 2.5 and six miles, with trainers tailing the field in SUVs to control small, whip-wielding robot jockeys that, years ago, supplanted a tradition of using children condemned by human-rights groups. Grammy Award-winning hip-hop producer Kasseem Dean, aka Swizz Beatz, has won multiple awards at the tournament with his team, Saudi Bronx. Discovering camel racing, he told the New York Times recently, “you enter into a whole other world.”

It was a revelation Paddy McHugh experienced throughout the early 1990s, as successive emirs invited him to dine and talk camels at residences across the Gulf. But he travelled to much poorer camel nations too, from Sudan and Somalia to Libya, where he partied with envoys of Dictator Muammar Gaddafi. “We went out after dinner,” he told me. “We stayed out all night. We drove around Tripoli and, oh man, it was like Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. It was amazing.”

The constant jet-setting lent McHugh a preternatural ability to code-switch, from Aussie roughnecks to desert royalty: to me he often spoke in a cheerful, avuncular tone he sprinkled with pre-watershed axioms I’d come to know as “paddyisms”. “I’m a billy, not silly,” he would say in response to a wild request; those who annoyed him were “dills”.

McHugh exported camels to New Zealand, the UAE, Thailand and Japan, and made a tidy living. But he despaired at how farmers back home would shoot camels and leave their bodies to rot on the ground. Camel meat and milk was a staple of diets across the world, and there was no reason, he believed, why Australians wouldn’t take to the animal if it were better marketed.

The best way to do so, McHugh concluded, would be to establish camel racing as a sport in Australia, and he asked a multitude of Outback towns whether they’d be interested in hosting the country’s first tournament. Boulia’s answered the call. It was a tiny cattle town, far from anywhere, whose nearby Davenport Downs station’s 3.73m acres was larger than Kuwait. Boulia’s best-known features were mysterious orbs of light called min mins that had terrified herders for centuries. Its mayor was ready for something new. He rallied townsfolk to build new toilets, shower blocks and bars, repaint gutters and clean little Boulia “from top to bottom,” McHugh told me. “They helped me like you wouldn’t believe. They were a godsend.”

“Crucially, the 1988 race had also caught the eye of Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, ruler of Abu Dhabi, who contacted McHugh about opening an Australian camel-export office.”

The “Boulia Desert Sands” opened in July 1997. It offered riders and crowds a “great sandy weekend,” and $20,000 in prize money. The weekend’s final victor won a motorcycle. Thousands flocked to the town, camping on grounds beside the racetrack, and within a few years Boulia was a highlight of the Outback tourist trail. It has continued to grow to the extent that organisers believe this year was its biggest-ever crowd. McHugh was visibly stunned as we reached Boulia on day two of our journey. Its single bar was bursting at the seams, and the racetrack was surrounded by a sea of tents and campervans McHugh reckoned to be twice what it had been in 1997.

A wire fence separated punters from the trainers, handlers and riders with whom we’d spend the next two nights. They call themselves “camel people,” and don’t like to take themselves seriously. Most encountered camels as unintentionally as McHugh had, and they are Mr Hydes to the jeroboam-popping Dr Jekylls of élite horse-racing—“proud misfits,” as one rider described them to me. Few employ the tactics of a Melbourne Cup-winning team, perhaps this is why Boulia’s bookies stick to a simple maxim: “A slow camel’s a slow camel,” one told me. “A fast one’s a fast one.” The riders were similarly sanguine. Camels “have quite a temperament,” said Chontelle Jannesse, who was competing in her ninth tournament. “They sense fear, and they sense people that are a bit dodgy.” Brettlyn Neal, who, in keeping with the misfit image, had been persuaded to ride her first camel having boxed a jockey in a circus tent, told me that “you hope you get a good start. And you hold on.”

Do not, however, confuse weapons-grade stochasticity with a lack of competitiveness. Each time a starter’s gun fired, and the roar of the crowd crescendoed down the straight, jockeys wh=ipped and grimaced as if Boulia were the only place on earth. Matt Anderson, who galloped home on a russet-coloured bull named Gunna to win the event’s showcase, three-quarter-mile run, broke down as he accepted his trophy. He had lost his father just days before, and the wife of his handler, and it was the anniversary of his sister’s death. “I was riding for a few people,” he said, choking back tears. “I did this one for my dad.”

The finale thrilled McHugh. It was, in contrast to the haphazard heats I’d witnessed previously, the passionate, professional face of Australian camel racing he wants to sell to the world. It will be no easy task. Alex Tinson, a UAE-based camel vet, has admired McHugh since they met on the 1988 race. “He’s one of those people who was just a camel-crazy,” he told me. “He’s a very unique personality: he gets on well with everybody, and he’s always a lot of fun.” But Tinson is unsure whether Australia and the Gulf can gel as racing cultures—they’re “on different planets in terms of performance.

“It’s like trying to race a Ferrari against a Trabant,” he told me. “I think there are too many roadblocks.”

The prospect of a global camel racing circuit is mouthwatering—but so is world peace. Formula One began in 1950 when a clique of wealthy European race organisers joined hands under the Paris-headquartered Federation Internationale de l’Automobile. Few camel nations could overcome the costs associated with hosting a major sporting event, not to mention the corruption and conflict that dog so many of them. Even McHugh concedes that his vision would probably only include Australia and the Gulf to begin with, and that the biggest challenge would not be to convince emirs to part with the yearly $1m he needs to get things going (“I’ve seen them spend a million dollars on dinner,” he told me. “It’s chickenfeed”), but to fly Boulia’s camel people to the Middle East. To kick things off, he told me, he’d like to train around a dozen Aussie riders and handlers over several weeks in Taif. “It would influence the Saudis a little bit to show that we’re serious, and we can do it,” he said.

This would mean, of course, dispensing with robot jockeys in favour of humans—and McHugh wants to scrap the Gulf’s endurance contests in favour of quarter-mile shootouts, filmed for TV in front of huge crowds, which he likens to the difference between Test and 20-over cricket. Another practice McHugh would like to eliminate is the nosepeg, a wooden stake driven into the soft flesh of a camel’s nose or upper lip, which is tied to a string to control the animal’s movements. McHugh and various animal-rights groups believe nosepegs to be barbaric, but they are still in use all over the world—including in Australia.

Even if, somehow, he manages to overcome all these issues, becoming camel racing’s Bernie Ecclestone is just step one in McHugh’s masterplan: to rehabilitate Australia’s out-of-control camel population into a thriving, multinational industry. He believes there are now around two million wild dromedaries in Australia, and it is thought they cause an annual $10m damage. Farmers shoot dead just 20-30,000 camels per year. They are a disaster waiting to happen. “You’ll never shoot camels out of Australia,” he told me. “The only way to control the population is to create a meat industry.” And the only way to do that, he believes, is to transform camel racing from a marginal Outback pastime into a major sport. “The camel is so underrated in Australia,” he added. “We need to lift that profile…racing is certainly a forum to do that.”

Organisers had awarded McHugh a lifetime achievement trophy before the final race, and he beamed as we left Boulia soon after. “Started with nothing,” he said, employing another, final paddyism. “Now it’s bigger than ‘Ben Hur’.” We spent that night four hours away in the town of Winton, and the following day we drove almost eight hours to Townsville, where I dined with McHugh and Virginia at their large, central home. Afterwards McHugh showed me his garage, which has become a shrine to his life proselytising camels to the world, crammed with trinkets and books and medals and posters. “You’ve got to have passions in life,” he told me. “I fell into it. And I’ve met the richest people in the world, I’ve met the poorest, been in goodness knows how many countries in the world: I’ve done some fabulous things through camels.”

His hair, now white as driven snow, is usually hidden under a baseball cap, and he has whittled his beard down to a well-kept moustache. He wears button-downs and chinos, and plimsoles rather than cowboy boots. McHugh is no longer a backcountry wildman. He earns most of his keep running guided tours to camel countries: just days after I left Australia he led a group to Mongolia, and he recently returned from Saudi Arabia, which reportedly hopes to feature camel racing in its bid for the 2036 Olympic Games. He claims to have trekked over 10,000 miles on camelback: if anything, it has taught him to treat life as a marathon, not a sprint.

Of course, he told me, there have been times he’s come close to giving up — “when I’ve thought, ‘What on earth am I doing here?’” But as Don Quixote, another hopeful wanderer, declared, “Too much sanity may be madness — and maddest of all: to see life as it is, and not as it should be.” McHugh still possesses the optimism of a man half his age, and Boulia, despite its madness, appeared to have reignited in him a belief that his camel racing dream could come true.

Aged 66, what choice does he have, but to continue down the wild path he’s been treading for almost 50 years. “Why not,” he told me. “It keeps me entertained—and broke.”