Matt Reeves had been dodging calls from Warner Bros. for weeks. He was smack in the middle of five to six months of intense post for War of the Planet of the Apes, the most ambitious film of his career to that point, and nothing was going to break his concentration.

He was huddled with a team of animators at Weta Digital, zoomed in 400% onto the face of the ape Cesar, his lead, agonizing over how to capture the nuance of emotion the scene required, when he got the umpteenth call from his agent. He hesitated, then he answered.

“So that meeting Warner Bros. wants to have. It’s not a general meeting,” his agent opened with. “It’s about Batman.”

Reeves excused himself from the animation desk.

Batman.

Matt Reeves was born in 1966, three months after Adam West’s campy Batman series debuted on television, and by five years old he was watching the reruns after school every day—same bat-time, same bat-channel—entranced by the character.

“The costume, the Batmobile, it was all very captivating. I didn’t see anything funny about it. I just thought ‘wow, Batman is really cool.’” Reeves tells us.

When he got into the comic books in his teens, he started to notice there was something more going on, a character with complexity that none of the others from the costumed set could approach.

“I’ve always felt that the Batman story was a very special story. He’s not really a superhero. He’s someone who’s driven by the pain of his past. He’s trying to find some way to make sense of his life. It’s a very psychological story. This is the character I relate to most,” says Reeves.

There was a version of that story he always dreamed of telling, a deeply personal one, and through Tim Burton’s two goth masterpieces with Michael Keaton, Joel Schumacher’s neon and cartoonish two with Val Kilmer and George Clooney and even Christopher Nolan’s grounded, human-focused Dark Knight Trilogy with Christian Bale, Reeves’s understanding of the Batman remained unexplored.

Unfortunately for him, the Batman script that Warner Bros. was pulse-calling him about wasn’t the take he envisioned. The script they sent over Ben Affleck had written for himself to star in, a film he originally intended to direct before deciding to step back.

“I read a script that they had that was a totally valid take on the movie. It was very action driven. It was very deeply connected to the DCEU, with other major characters from other movies and other comics popping up. I just knew that when I read it this particular script was not the way I’d want to do it,” Reeves explains.

Even as the countdown clock was on for him to turn in Apes, he decided to go to Warner Bros. in person to respectfully tell them no.

“I said look, I think maybe I’m not the person for this. And I explained to them why I love this character. I told them that there have been so many great movies, but if I were to do this, I’d have to make it personal, so that I understood what I was going to do with it, so that I know where to put the camera, so that I know what to tell the actors, so that I know what the story should be. This take, I told them, pointing at the script, is a totally valid and exciting take. It is almost James Bond-ian, but it wasn’t something that I quite related to,” Reeves says.

“So what I’d love to do, if you’re interested, is I’d like to get involved and find a way to take the story and make it very, very personal and get to the place I want him to be, to make it a Batman story and give him the arc, and have the story rock him to his core. It wasn’t going to be another origin story, not with Ben already in the character. But that’s what I would do,” Reeves told them.

Before they got too excited, he dropped the kicker, intended to scare them away for good.

“I said, but here’s the other thing. This is why I think you’re not going to want me to direct this movie. I can’t even tell you what that story is, for months, because I have to finish this Apes movie. And to my utter shock and surprise, they said, ‘you know what, we really would like you to do this. And we will wait.’”

By the beginning of 2017, as he put the finishing touches on Apes, a transition started happening. Ben started reevaluating what he wanted to do, Reeves says. That’s putting it lightly. Ben was fighting through perhaps the hardest year of his life—and Batman became the least of his concerns.

“We had no idea what was going on,” Dylan Clark, Reeves’ long-time producing partner, tells us. “Ben is a friend of mine, and I love Ben, but I didn’t know exactly about those things were happening in his personal life. [We didn’t find out] until much later.”

Affleck stepped away entirely, leaving Reeves and Clark with a blank slate. Now, their version of The Batman could be anything. So, riddle me this, Reeves—what’s going to be? What is this idea that you were holding so close to your chest?

“I hadn’t worked out the story. I had this north star of a guiding principle. Then the fact that there was this moment of transition, out of that came an opportunity to say, ok, what if we didn’t do another origin tale? What if, instead, we went to the imperfect Batman of his early days?”

There it was, something to build towards—Batman: Year Two.

“A lot of the Batman stories we’ve seen on film, you see an origin tale. You see his parents killed, and then you see him perfecting himself into becoming Batman. A lot of times you see stories where he’s already become Batman, then the Rogues’ Gallery villain comes in, and it’s then their story, and you watch him go toe-to-toe with them,” says Reeves.

“I wanted the main character in the story to be a Batman who was a year in and still trying to figure out how to do this, how to be effective, and he’s not necessarily succeeding. He’s broken and driven. He’d like to think that he is doing the right thing, that there’s another part of him that’s struggling right up against the limits. I think his biggest weakness is not realizing the extent to which the person that he’s fighting is himself.”

Reeves’ Batman, then, is not Batman yet—he just thinks he is. And there are still truths for him to face, secrets he must uncover, before he becomes the man he thinks is.

But who should play such a Batman? Reeves, ever the movie fan, thought long and hard about actors he’d seen capture that spirit best—someone who could be believable both as both the man of action throwing criminals into Arkham, with a subtext that he could be a patient at Arkham himself.

Brainstorming with Clark after a long, painstaking script-writing stage, Reeves thought of one of the best movies, and best performances of the last decade—Good Time (2017), starring Robert Pattinson.

“Rob had just been doing these amazing parts with these incredible directors, and showcasing all of these skills. Good Time was a movie we just marvel at. He’s so real, he’ so intense. There was an emotional arc, a trajectory that really resonated with us,” says Clark.

Pattinson, they felt, was the only actor who could capture the layers that they needed their Batman to possess, a man of vengeance and of hope, an obsessive, near-delirious man who remains clear-eyed, who can still represent justice in an unjust world.

“You really have to find an actor that has a lot of chops. We were blessed that Rob wanted to do it, because he has those abilities. He is that talented,” says Clark.

“I just knew there was something radically different from anything we’d seen in Batman movies before,” says Pattinson.

“Right from the beginning there’s a desperation to him. He’s really working out this rage. All the fights seem very personal. He wants to inflict his kind of justice. He’s just compelled to do it. There is no other option,” Pattinson continues.

Just because this would be a story about Batman first and foremost, however, doesn’t mean that the Rogues’ Gallery wouldn’t play a critical part, they just wouldn’t be the heart of the story, as Catwoman was in Batman Returns, The Riddler was in Batman Forever, Mr. Freeze was in—well, you get the picture.

Most important to Reeves was that this would feel like a detective story, the 50s film noir kind, where the naked city is all that matters, and wading through it means inspiring the wrath of any number of shady characters.

First up on his list—a serial killer.

“I knew very early on I wanted a serial killer type story, where the killings would reveal this cooperation between the people who are legitimate pillars in the city and the criminal element in the city. I wanted those things to be entwined,” says Reeves.

“Batman is investigating these crimes, all of which point to the history of the city, and that history eventually comes back to his own family history. It starts to shake his very core, and causes him to have an awakening, and to change.”

While he was asking himself over and over about Batman’s costume—why a man would wear a costume like that to begin with—he started thinking of a man who worn one in the real world, one of the most notorious serial killers in American history.

“I started thinking of the Zodiac Killer, because he did create a costume for himself and he wore a black hood, he had his own insignia. He was an early anti-superhero, a scary figure who terrorized California,” says Reeves.

Perhaps if the Zodiac Killer were in Gotham, he thought, he would leave ciphers for Batman instead of the San Francisco police.

“That immediately made me think, oh, that could be a brand-new version of the Riddler,” says Reeves.

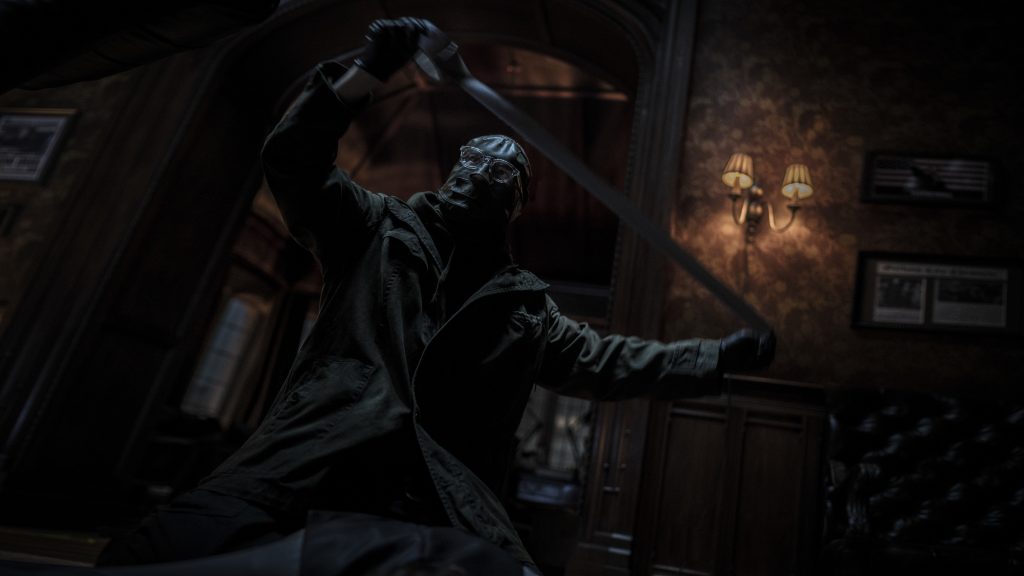

Reeves’ Zodiac-Riddler, so to speak, would be Paul Dano, who had previously done a masterful job embodying monstrous and tortured souls in films such as There Will Be Blood (2007), Prisoners (2013) and 12 Years a Slave (2013).

Even with that kind of a resume, Dano still found this version of the Riddler to be a daunting task, one that unsettled him so deeply he couldn’t bring himself to prepare for it alone at home.

“I read quite a bit about serial killers in general, which wasn’t light reading. I found it so challenging that I had to go to the coffee shop and read. I just needed more friendly surroundings to read that stuff,” says Dano.

Dano also found, the more he studied the script, that his Riddler was more than just a Zodiac Killer with a question mark stitched on. The character that Matt would write had the same emotional complexity of his Batman—he was a human, too, one shaped by the world that raised him just as Bruce Wayne was.

“I realized, Batman is born in trauma. And so are some of the ‘villains’,” says Dano.

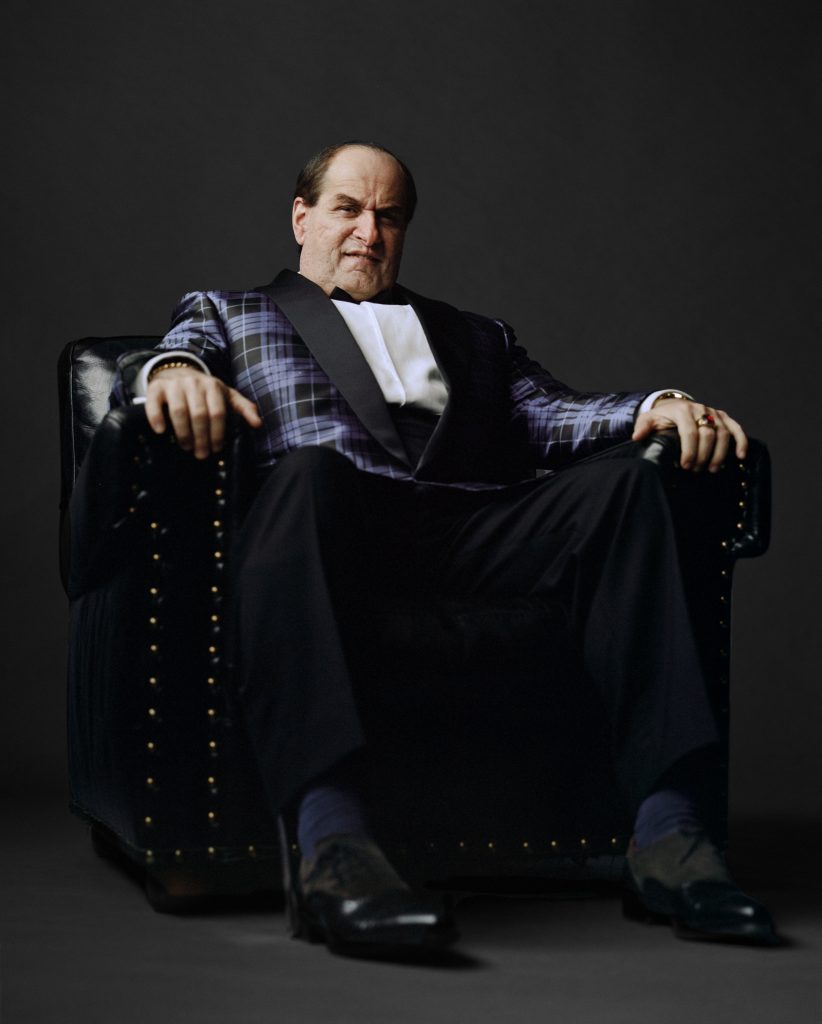

As Batman raced after Gotham’s latest serial killer, leaving him clues as to how he was choosing his victims, Reeves’ started to see other classic characters appear in his mind’s eye. Perhaps he wandered into a nightclub and met its proprietor The Penguin, still in the early days of his career, before he achieved kingpin status. Maybe he would follow the city officials and gangsters that populated the nightclub, along the way running into Selina Kyle, the Catwoman. Perhaps one of the gangsters was Carmine Falcone.

“It was never an attempt to say like, hey, let’s just have every single big Batman character that you could possibly have. It was more asking, how do we tell the story in such a way that we reveal the classic Warner Bros. noir fabric of Gotham, and then that just presented all of these opportunities to have new versions of classic characters. And that was really exciting for me,” says Reeves.

As he assembled his cast further—Zoe Kravitz as Catwoman, an unrecognizable Colin Farrell as Penguin, John Turturro as Carmine Falcone, Jeffrey Wright as Commissioner Gordon, Peter Sarsgaard as District Attorney Gil Colson and the Cesar the Ape himself Andy Serkis as Alfred Pennyworth, he started peppering them with touchpoints, films to watch and study that would help them get the idea of what he was going for.

“He was talking about a lot of films that I really respected like Taxi Driver that were really character driven. With a lot of those references, I thought, ‘oh, you’re going to be interested in people? And what makes people do things?’ And, yeah, that’s what Film Noir is. It’s not just an aesthetic, it’s really an investigation of the dark side of ourselves,” says Sarsgaard.

Some of the references weren’t cinematic at all.

“He even actually mentioned Nirvana, the music group, on one of the phone calls, because how do you communicate tone to actors? You’re creating a world that exists in a parallel universe to ours, and that needs to have authenticity. How do you describe that world? It’s one step at a time, a thousand tiny pieces,” says Sarsgaard.

If there was one rule for Reeves as he was casting, it was picking actors who fit best in movies in which capes were not a primary feature—the Brooklyn contingent, Turturro calls them.

“You could tell by the casting what he was going for. You started hearing about who else was in the film, and incidentally we all live within a couple of blocks of each other,” says Turturro. “There’s at least five of us in the film that could walk to each other’s apartments.”

“A lot of times, credible, really smart actors don’t want to be in a comic book movie. Matt has a lot of credibility in the movie making space with actors, so I think they all wanted to go on that exploration with him,” says Clark.

“I think what really it comes down to is Matt created on the page characters that were very distinct and had really rich backstories and these actors were able to come and do their thing.”

It is in their complexities that the soul of the movie lies.

“Matt, as a filmmaker, is someone who concentrates on the emotional heart of a story. And I think in this case, that heart beats very, very, very loudly underneath this dystopian Gotham,” says Serkis.

The Batman’s Gotham, too would have socio-economic complexities that the films in the past had left unexplored, something that led Jeffrey Wright to sign on.

“In Matt’s Gotham, the tendrils of class are evident in a way that we haven’t seen before. We see the interstitial tissue of class; we see the tensions there. There are assumptions that other films made that he didn’t make, dynamics that Matt exposes and allows us to live in the storytelling more vividly because we didn’t take things for granted. And that directly informs the relationship between Gordon and Batman,” says Wright.

Matt Reeves may have finally told the psychological noir Batman he’d always dreamed of, one that checked all the boxes of what he hoped a Batman story could be, but while he didn’t want the story to interact with other aspects of the DC Expanded Universe, he didn’t want this story to be a one-off like Todd Philips’ Oscar-winning Joker. While this may be ‘year two’, his Batman sets up a world built to sustain many years to come—stories he hopes he can tell himself.

And while he believes his Batman is perhaps the best version ever, as big of a fan as he is of previous iterations, he by no means wants his Batman to be the end of the character, the final way to reimagine him. Batman is built to be reimagined and recontextualized into each generation, and while his Batman is nearly out in the world, other filmmakers are still carrying their Batman with them, not yet telling a soul until perhaps Warner Bros. makes the same call to them that they once did him. And that excites the hell out of him.

“There’s no question it’s going to continue on long after this. It’s great, because it’s a great myth. It allows itself to almost endless reinterpretation. There’s been so many iterations ,and what was important for me, critical for me was, I could not go into doing this one without feeling like we would have something definitive to stay to say about this myth,” says Reeves.

“I think that a lot of these great myths have that power, which is that if they truly resonate, they allow you to find a way to take the aspects of it that people love, and then do something new with it. And then people connect to it all over again. And I hope that’s what we’ve done.”

The Batman is in cinemas on March 3 across the Middle East