I discovered that there are (at least) two Mark Ronsons. Mark 1 is a thoughtful intellectual. The kind who ponders every word before speaking, who with shy confidence slowly guides you into his inner world and opens the treasure chest of his creative process, honed in a lifetime of total immersion in music and meticulous attention to every detail, every beat, every note in the studio.

Mark 2 is the multi-instrumentalist stage animal who closes the Montreux festival in a double-breasted suit, live scratching, guiding the audience like a rockstar, directing a band of nine of the best soul and jazz musicians in the world, the deus ex machina of a sound construction that —clearly—fills him with joy. When Mark 2 delivers what Mark 1 has designed in his head, magic ensues.

I met Mark 1 in Montreux on the morning of the concert. His slender wearing a faded t-shirt, a pair of bottle-green glasses on his head that he won’t remove. He enters the room where I am waiting, asking permission to come in.

He sits on a corner sofa that seems too big for him, but his presence, his concentration, contrasts with his physical appearance. He looks younger than his 48 years. It’s clear that this will be a genuine interview, that he’s here to talk, and do so seriously, for as long as we need. There are many other people in the room, but they keep a respectful distance.

At first, he seems tired and a bit detached, but I quickly learn that it is all part of his process—his way of connecting with reality. He seems to enjoy standing a bit to the side, watching from the wings. It’s how he often positions himself even when among others.

I had observed him the night before, at a dinner, having just arrived in Switzerland with his wife Grace Gummer—daughter of Meryl Streep.

The couple stayed apart for a long time, him gently cradling her lap, or assisting her as she applied eye drops, or applauding from behind a column during an impromptu jam session of musicians in a lakeside cottage that once belonged to Claude Nobs, the festival’s founder. His eyes are always a bit wide, his gaze revealing more than he might wish, his head often slightly tilted, the same pose an animal might take when assessing a situation.

There’s only one taboo topic: we won’t discuss the soundtrack for Barbie, which Ronson produced, but at the time of the interview was yet to be released. It consisted of a diverse ensemble of stars including Dua Lipa, Nicki Minaj, Ice Spice, Lizzo, Charli XCX, Tame Impala and Billie Eilish.

From all the work you’ve done, it’s very hard to pinpoint your taste. You constantly jump between genres. How do you do it, and what ties them together?

The first album I produced, almost twenty years ago, was by Nikka Costa. Over such a long span, if you truly love many genres of music, you evolve, jumping here and there. I could never imagine doing just one thing; I’m not judging those who do. But I love soul, jazz, funk, rock, hip-hop. I grew up listening to all these genres, a somewhat schizophrenic childhood, musically speaking: I always liked DJing, but my stepfather was in a rock band. I’ve been very lucky. Sure, looking back, there are also some projects that in hindsight make me say, “Maybe I went a bit too far here.” But, at the core, the music I truly love usually has a great melody, a great vocal or instrumental performance, and a great groove, a great rhythm. If you think about it, you can say this about many genres, from Fleetwood Mac to Earth, Wind & Fire, to A Tribe Called Quest and Quincy Jones. Groove and melody are universal, common to many genres.

When Audemars Piguet announced that you would produce the closing night of the Festival, you stated that the lineup would be “the best band I’ve ever put together.”

These musicians are the ones who brought some of my best records to life. So it is the best band I’ve ever put together. Montreux is not just any festival; it’s an event that celebrates music, representing so many different things. But for me, in my head, it’s Aretha Franklin. It’s Miles Davis. It’s Nina Simone. It’s Curtis Mayfield, the Average White Band, all these incredible soul and funk records that I love, that made me fall in love with music.

I really wanted to do something special. Then I had this idea of bringing some of my favourite musicians to perform with their bands. I thought, well, if we have all of them here during the evening, these musicians who played on all my records, from “Back to Black” to “Uptown Funk” to the productions for Rufus Wainwright, we could do something really special at the end of the night, something we’ve never done before. Bring those songs to the audience, perhaps performed just once by the people who created the magic in the studio.

Guys like Tommy and Homer, the bassist, even after recording “Back to Black”, only did six or seven concerts with Amy [Winehouse]. Then Amy went on tour with another band, so the opportunities were few. All these musicians over time have built successful careers, writing other songs. Some of them, the core group that played on “Back to Black”, haven’t played together in the same lineup that recorded the album.

It’s really special and moving. When you listen, you think: “Damn, it sounds like we’re recording the album.” It could be like the first day when we hit the record button. Like it was, for example, for “He Can Only Hold Her”.

Lastly, having Yebba here is really important. To honour and celebrate Amy, one of the greatest singers of all time, you definitely need someone very special. I truly believe that Yebba is one of the best singers of her generation, and I also think she has incredible courage and talent to stand up and say, “Yes, let’s sing something by Amy,” while bringing her own personality to it all.

How was it to reunite them, how did you work together?

We practiced like crazy, also because I’m a bit anxious. We practiced to the point that some of them wanted to kill me. They are super-professionals, musicians who learn a song in five minutes and play it on Jimmy Fallon [host of The Tonight Show] that same night. I’m not like that; I need to play, to practice.

We learned 18 songs that we had never done before. All in five days. In some of the sets, I DJ a cappella while the band plays. There are a lot of things that could go wrong, go haywire. There are no computers to correct; we’re live. Risky but fun. Even if we mess up, they’ll be wonderful mistakes [that evening I’ll notice only one mistake during the performance. It indeed was extraordinary, almost as if it served to remind how fragile and hard to achieve harmony and perfection can be].

You won an Oscar for “Shallow”, a Golden Globe, seven Grammys, an endless list of other awards. Is there one you’re particularly attached to?

If you ask me to choose one, I’d say Producer of the Year for “Back to Black”. In the end, I feel more like a producer than an artist, and for this, it’s important to have someone tell you, “Hey, this year you’re the best producer.” Whatever these awards mean, I think that one really concerns the essence, the craftsmanship I feel in my work.

You’ve produced and composed for some of the biggest stars in music. How do you prepare for each of these projects? How do you bring out the best in each of the artist, taking them where they usually don’t go?

I try to listen to them, to understand them. I could have had an entire album ready in my head before seeing Lady Gaga. But she comes into the studio that first day, expresses a certain emotion, a song. My job is to chase that emotion, try to catch it.

My friend Richard Russell, a great producer, says that this job consists of being constantly in tune, making a series of right decisions, continuously. Try to intuitively understand what’s happening to the artist. Then, of course, there’s the writing, the arrangement.

When I started working with Lady Gaga on “Joanne”, something happened. She loves jazz, and given my previous work with Amy, for all these reasons, I guess she had the idea that maybe we’d make a jazz record. We were in the studio, trying to understand each other, and she said, “You love jazz, right?” And I said, “Yes, of course, but I don’t know it that well.” I like funk, soul, but I can’t write orchestral arrangements like Quincy Jones. Anyway, she was trying to push me in that direction. I looked at her; we were in a studio in Malibu, California, she was wearing jean shorts, cowboy boots, and a hat. Suddenly I felt drawn to Country, a kind of Stevie Nicks [musician, soloist, and singer of Fleetwood Mac] vibe.

We started working on “Joanne”, a song she was writing. Initially, it could have been a jazz tune, then almost fingerpicking, very acoustic. In the end, it turned into something completely different, which led to the album and also the genre of A Star is Born. I always try to have an antenna ready to pick up, to be aware of the direction we might take. It’s right to be prepared for everything: you go into the studio on the first day, you have to be open to every possibility. Ready to change direction continuously.

You’re a good listener.

I think it’s the most important tool for a producer. Emotional listening. Producers must constantly hear the arrangements, the music, the melody, the harmony. But ears can be useful for much more than just the technical listening of music.

Did you immediately realize that some of the musicians you met would become stars?

I think if there really was something you could sense, like Clive Davis [the producer who discovered Whitney Houston], then I’d be much richer than I am!

I can only say if they have something that moves me, that I’ve never heard before, if they have a sound so unique that nothing and no one resembles them. Also, even if I were able to feel that they are extraordinary, it’s not certain that I would be able to help them release that hidden gift.

But I find it really exciting to work with artists who are just starting out because it’s all new, so exciting. It takes me back to my beginnings when I felt the same way. It’s an energy. Like drinking from the fountain of youth.

At this point, you are more than a spokesman, I would say almost a curator for the Audemars Piguet music project, aren’t you?

Yes, it’s a very fruitful collaboration. We couldn’t do this show tonight without AP. They are patrons of the arts. François [François-Henry Bennahmias, CEO of AP, ed] is passionate about music and when we first met and talked, one of the first things that came up was Montreux.

Let’s be real: tonight’s show is financially demanding; I’d have to play here for three weeks in a row to afford all of this, and I’d probably have to DJ at every party after the show and wash dishes at the restaurant on the terrace. So, of course, I am very grateful. Every time with them, the project has been different. I think it’s always important for AP to lift the bonnet, so to speak, and show the audience the creative process: the first time, Lucky Daye and I made a song together, filming its video on that very day.

For tonight, we started a collaboration with Daphnée Lanternier, who created an incredible conceptual set design. The thing I regret is that we are only performing one night. It’s like the only time I can go on stage and feel like I’m in Daft Punk. Anyway, every time we manage to think of something interesting and really try to create art. We’re not just here for branding.

I chosen a selection of some of the most successful songs you’ve produced. Can you tell me something about each one?

Okay.

“Ooh Wee” ft. Ghostface Killah and Nate Dogg

Ah, that one. I’m proud of it. A month ago, I did a surprise DJ set in London with a friend, who has this truck with a system, speakers, and so on. Something announced an hour before. About 200 kids showed up, and I started with “Ooh Wee”. It’s a song that’s almost twenty years old, born with Nate Dogg and Ghostface Killah, the one that brought me to Montreux for the first time in 2004, and it still works, sounds so lively. I’m proud of it. And I’m grateful for that record; I have a perfect song to start a DJ set with a hip-hop sound. It always rocks.

“Littlest Things” ft. Lily Allen

This takes me back to an intimate time. It was before I had success as a producer. Lily Allen was so brilliant. A couple of her singles had come out and were doing well. She came to New York; we were friends, and I think she was twenty. We went around the city to record stores looking for tunes to sample. It’s a bit like rummaging through the trash, something like that. It seems to me that the piece we sampled was in the soundtrack of Emmanuelle, the ’70s film. I think the piano comes from there. Anyway, I put the record on the turntable, put on my headphones and said, “Cool, Lily come here.” She listens, she likes it. We went back to the studio and within an hour the song was born. That’s how I ended up opening her tour, just as she was blowing up in the US. It was really fun.

“Back to Black” ft. Amy Winehouse

This is a bit of a whirlwind memory, a kind of memory tornado. I met Amy at three in the afternoon, I think it was a Tuesday. She came to my studio in New York. We sat down and talked about music. Usually, when a singer comes to me, I already have songs for her to listen to: “What do you think of this, what do you think?” But she was so fantastic, special, unique. I knew I had nothing new to impress her with, and she was leaving for England the next day. She would only be in New York for one day. I said, like, “I have nothing for you to listen to right now, come back tomorrow.” You know, I stayed up all night because I wanted something that could work. I kept telling myself, “Amaze her, make her stay.” The beginning of the piano and the drums of “Back to Black” came out. She liked them, she stayed in New York for another five days. She wrote the lyrics in half an hour, I burned the track the old-fashioned way, on CD. She went to the back, the track was maybe only a minute and a half long, she started listening to it and rewinding it to write the lyrics. It was pretty crazy.

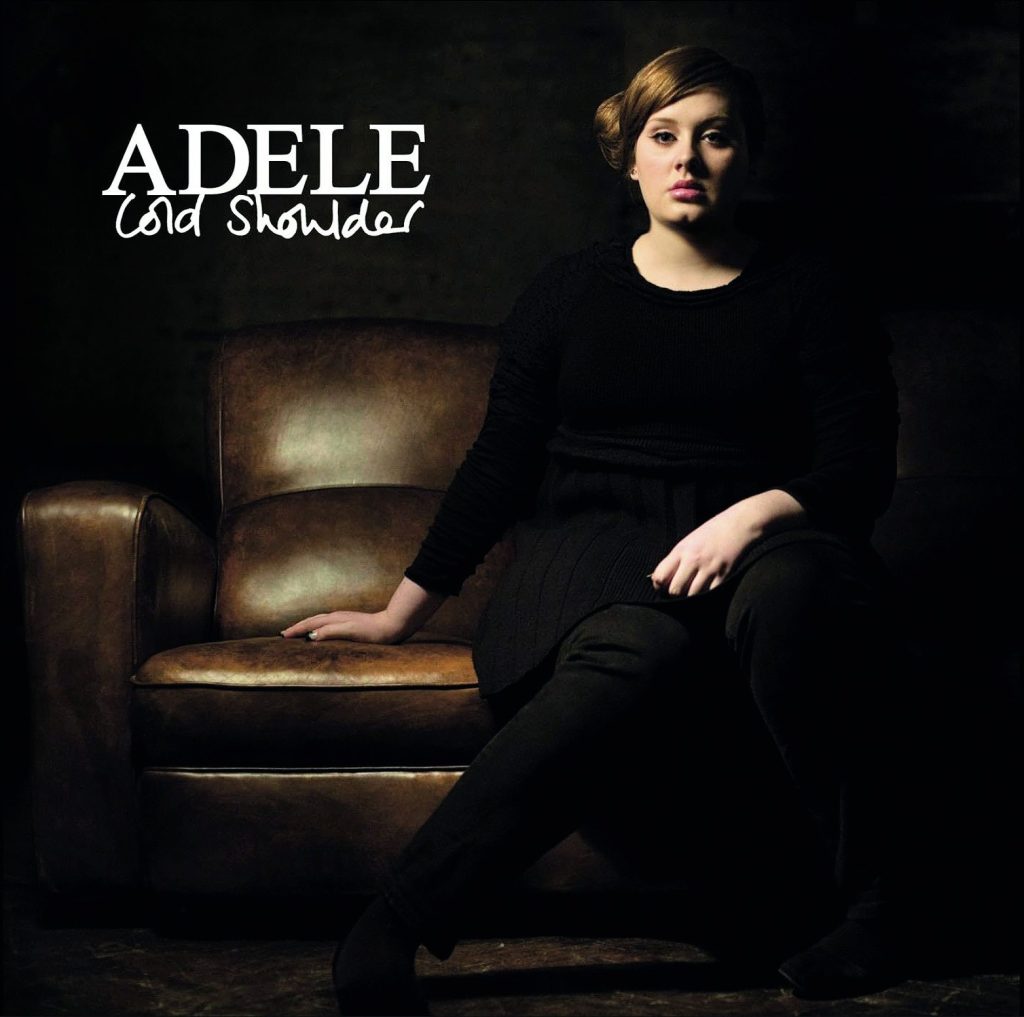

“Cold Shoulder” ft. Adele

It was because of Amy. You know, working with her was what made me famous. Richard Russell, the founder of XL Records, said to me, “Do you want to come and meet this girl, Adele?” I walked into his studio and there was a big sofa, pretty much like the one we’re sitting on now. She looked like an 18-year-old girl, sitting cross-legged. She wouldn’t stop smoking. This is Adele, they told me. And I was like, “Oh, nice to meet you.” And she said,

“My pleasure. I have this demo, the song is called ‘Cold Shoulder’, I’d like to know if you’re interested in producing it.”

I listened to it, it was cool, just her and the Wurlitzer piano. I don’t know why I said it, maybe I was a bit greedy, or I felt I had to say something, or I was hungover, so I said, “Oh, cool. Are there any other songs?” And she said, “No, it’s just this one.” It was basically take it or leave it. “Do you want to work with me? This is the song I’m telling you to produce.” That’s how it went.

To be honest, I wish I had done a better job on that song. It was a time when I had just had my first hit. I was running everywhere, I was on tour. We went to a different studio than usual, with musicians and engineers I didn’t usually record with. We had one day to do this song. In hindsight, I wish I had done a little better, with the sound and production. Anyway, I mean, it’s still great and, of course, her voice is amazing, so whatever.

“Mirrors” ft. Wale

Yeah, cool. I remember Jay-Z heard that beat, but I had already promised it would be for Wale. I think a good friend of my manager at the time said, “You know, Jay-Z heard that beat, he wants it.” And I said, “Oh my God, I don’t even know what to say… Of course, it’s a dream that Jay-Z wants to collaborate with me.” But I had already promised the beat to Wale, he was a friend of mine, as well as an artist on my label, and of course, there’s also Bun B on the track.

I love that song because hip-hop is one of my greatest musical loves, but it’s not a predominant part of the music I’ve made. For some reason, I took my love for hip-hop and percussion and fused it with other musical genres. I took the influence of hip-hop and combined it with Amy or whoever else. But there are some tracks in my career, like “Mirrors” and “Fried Chicken” with Nas and Busta Rhymes, maybe a few others, that I’m

very proud of.

“Alligator” ft. Paul McCartney

Working with Paul McCartney is scary because not only are you there with, you know, maybe the greatest songwriter/producer/arranger of all time, but you’re also there with a Beatle. It’s a lot of pressure. I remember the first time I met him, he was so nice. He was like, “Hey, Mark, how are you?” And I was like, “Oh my God, he knows my name.” It was a bit like that.

We were in the studio and he was playing the guitar, and I was like, “Oh my God, this is Paul McCartney playing the guitar.” It’s a bit like that. But he’s so nice, so kind, so generous. He’s a genius. He’s a genius in the way he plays the guitar, the way he plays the bass, the way he sings, the way he writes songs. He’s a genius in every way. And he’s so humble, he’s so kind. He’s a real gentleman.

I remember when we were working on “Alligator”, I was playing the drums, and he was playing the guitar, and he was like, “Mark, can you play the drums a little louder?” And I was like, “Of course, Paul.” It was a bit like that. It was a great experience. I’m very proud of that song. It’s a great song. It’s a great collaboration. It’s a great memory.