In the final pages of Alan Moore’s seminal Batman story The Killing Joke, The Dark Knight finally asks the question that has tortured him, and us, for nearly eighty years:

As he chases the Clown Prince of Crime through, appropriately enough, a hall of mirrors, Batman finally bellows at his nemesis: “I mean what is it with you? What made you what you are? Girlfriend killed by the mob maybe? Brother carved up by some mugger? Something like that, I bet. Something like that . . .”

Joker, who in the previous twenty or so pages, has among other horrors shot and crippled Barbara Gordon, kidnapped Commissioner Gordon, stripped him naked and bombarded him pictures of his paralysed daughter, pauses to reply: “You know, I’m not exactly sure… sometimes I remember it one way, sometimes another. If I’m going to have a past I prefer it to be multiple choice!”

This, as an answer, is flamboyantly unhelpful. But it is the punchline to a thunderingly brilliant meta-gag, which is what it turns out The Killing Joke is. Because a fair part of the story has in fact been a highly detailed origins tale for the fright-wigged freak.

A great deal of ink has been spilled with exceptional skill by artist Brian Bolland on sketching out, in beautiful, moody, faded sepia, Joker’s beginnings as a failing stand-up comic whose wife has died in a tragic accident, and who plunges into a vat of acid emerging horribly disfigured and mad as a bag of badgers.

All that, the final frames reveal, may be so much baloney. The very book in your hands is a punchline, you are the butt of its joke and at the end as in the dark about who Joker is as ever you were. “Sometimes I remember it one way, sometimes another.”

Jeeze . . . where in the heck do you start trying to tell the life-story of guy like that?

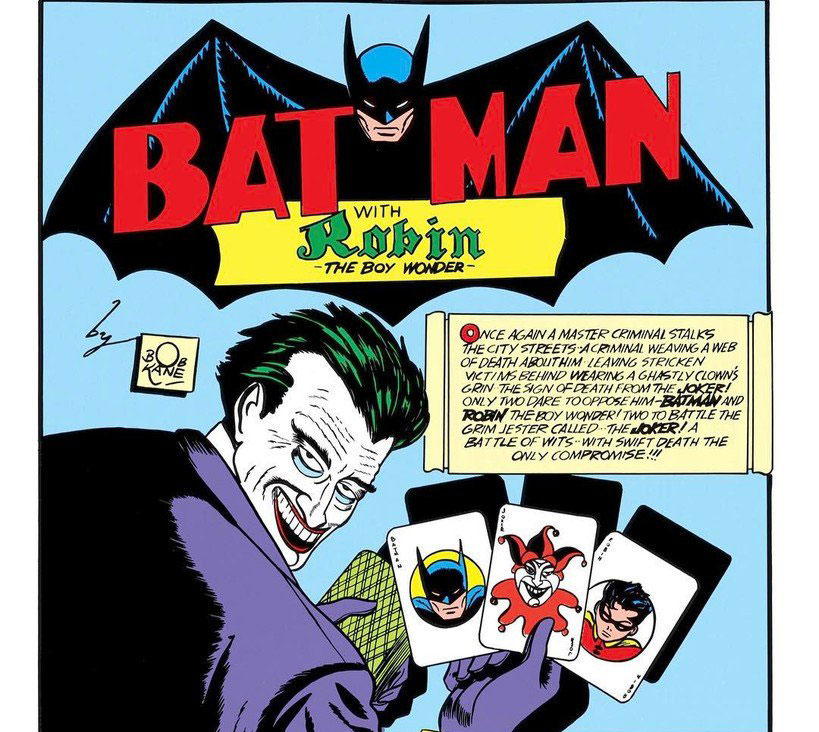

In early 1940, during what was the height of what would become known as the Golden Age of Comic Books, Batman creator Bob Kane, then a US$40-a-week freelancer, found himself on the lookout for a villain.

The Caped Crusader had already appeared in Detective Comics the year before, a hurried response to the unexpected success of Superman who had unfurled his scarlet cape in 1938. But for Batman’s debut appearance in his very own comic book Kane wanted a villain to match the occasion.

But who among the troika of writers and artists who worked on that first issue actually nailed the character of Joker remains hotly contested.

“With early Joker creative origins there’s an awful lot of debate,” says Kingston University’s Will Brooker, Professor of Film and Cultural Studies and author of three books on Batman. “These people were in their early 20s in the late 1930s and as Batman got more profitable, they all subsequently argued about who had had the idea for Joker.

Bob Kane was certainly the loudest voice, Bill Finger, who was the writer, has only been added to the creative credits quite recently. Jerry Robinson, the artist, is even more marginalised. Even when they were alive, you basically had these old guys arguing about who came up with the idea.”

The soup of influences from which The Joker emerged in Bob Kane’s studio included the notion of a ‘jester type’, a publicity image of actor Conrad Veidt in a 1928 silent movie The Man Who Laughs a joker playing card and a poster of a grinning dummy that Bill Finger had supposedly seen in front of a ride on a trip to Coney Island. But exactly who brought what to the table and when remains hotly disputed.

“Bill Finger and I created the Joker . . . Jerry Robinson [later] came to me with a playing card of the Joker. That’s the way I sum it up,” Bob Kane said before his death.

Whatever the truth, Batman #1, published by Detective Comics in Spring of 1940 (later to become DC) was an instant success. More of a surprise was the wild popularity of Joker, who Kane & Co. had only intended as a one-off character, originally eschewing the idea of any recurring villains. After all, if the Caped Crusader couldn’t dispatch his foes for good and ever, what was the point of him?

In the final frames of the original draft of Batman #1 Joker was, then, killed, stabbing himself by accident with his own knife. But as the issue was about to hit the printers senior editor Whitney Ellsworth spotted brand potential and ordered Kane to add a final frame of Joker, apparently alive, in an ambulance.

The Joker of Batman #1 and its subsequent issues was a significantly different character to the one who would emerge in the modern era. The Batman stories of the 40s and 50s were more concerned with detection of crime, with Batman as a Sherlock Holmes figure, and Joker his frazzle-headed Moriarty.

But what is evident even in those early strips, and what differentiated Joker from the dozens of other eccentric, half-forgotten villains that Batman battled in weekly instalments, was that in essence he was the anti-Batman, an existential threat to Bruce Wayne’s ordered world: each was a distorted, uncomprehending reflection of the other’s core values.

“A really important idea that is there, I think, is that of the King’s Jester,” says Brooker. “The character who mocks the figure of authority. Batman is known as The Dark Knight, so his character obviously is a serious authority figure. It’s similar to King Lear where The Fool is the King’s counterpart, mocking and pointing out the King’s weaknesses.”

Joker was, then, not just another hood in a wig but the anti-Batman, whose very existence is an affront to Joker and vice-versa. The pair face off in an eternal struggle, not so much good versus evil, but order against chaos – The Dark Knight’s somber, pure black yin hopelessly and forever entangled with Joker’s neon-green, crazy-ass yang.

For almost a decade Batman and Joker would do regular battle on the inky pages of DC comics. But trouble was ahead. Joker was about to meet his deadliest foe and he came in the form of a young, very angry psychiatrist by the name of

Dr. Fredric Wertham.

On Tuesday, October 26th, 1948 the children of Spencer, West Virginia, burnt their comic books. Led by a small, dark-haired boy with piercing blue eyes called David Mace they assembled in front of a vast pyre built in the schoolyard, the result of a door-to-door campaign waged with pushcarts and bicycles.

“Do you, fellow students, believe that comic books have caused the downfall of many youthful readers?” Mace intoned. On receiving the murdered assent of the pimpled conclave Mace stepped forward to the bonfire, and lit a match. “Then let us commit them,” he said, and, set the thing ablaze.

He wasn’t the only one. These latter-day book burnings happened all across the states, while newspaper and magazine headlines hammered home the new threat to American Youth. A NATIONAL DISGRACE! COMIC BOOK INSPIRES BOYS’ TORTURE OF PAL!

Comic books, and their heroes and villains, had suddenly become public enemies number one. As recalled in journalist David Hajdu in his book The Ten Cent Plague, the panic of the late 1940s and 1950s affected the entire industry, driving it into a recession both financial and creatively from which it never really recovered.

The brouhaha had been born of a campaign waged by Dr Frederic Wertham. Wertham, a psychiatrist of dubious academic respectability but a gimlet eye for self-publicity didn’t so much argue as boldly state with little or no evidence that comic books were at the root of America’s problems, from juvenile delinquency to bedwetting. “We found that comic book reading was a distinct influencing factor in the case of every delinquent or disturbed child we studied, and that factor must be curbed,” he declared in his page-turning jeremiad against comics, The Seduction Of The Innocent.

A major plank of Wertham’s objections to Batman was his assertion that comic books undermined youths’ natural respect for authority. Given that Joker’s defining characteristic was his maniacal opposition to authority in any form whatsoever it is not surprising that his character was one of the hardest hit by the ensuing clampdown. In 1954, in an attempt to stave off legislation, the industry established the Comic Code Authority. Henceforth the depiction of ‘policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority’ was forbidden. Comics, meanwhile, would bear a stamp, guaranteeing their wholesomeness.

“From the early ’50s you have the comic book panic and the move towards censorship, for various reasons, the violence but also the sexuality,” says Will Brooker. “After the Comic Book Code everything was defanged, and that takes various form, things become less violent, characters are given girlfriends and so on. And Joker becomes more playful and more clownish rather than a [dangerous] jester.”

It was a situation that endured for nearly two decades, with often Joker giving way to plots involving interstellar creatures and elves. But like many attempts at repression, this one gave rise to odd and unexpected symptoms. In 1965 television executive William Dozier, a man who freely admitted to never having read a comic book in his life, found himself tasked with putting together a pilot for a Batman TV show for struggling American network ABC. On a flight from New York to Los Angeles he read a few samples he’d had an assistant pick up, and was baffled as to the franchise’s enduring popularity.

“I thought they were crazy if they were going to try to put this on television,” he later said. Dozier’s reaction to the source material might have been different if the comics he had read had been from Batman’s Golden Age, but the issues he had perused at 33,000 feet were recent examples, all bearing the miserable CCA seal of approval.

With such thin material to work from Dozier decided to reimagine Batman as a kind of Pop Art Pageant, an Andy Warhol print brought to life, goosed with on-screen POW!!!s and WHAMMO!!!s lifted straight from Roy Lichtenstein. “I had just the simple idea of overdoing it,” he said. “Making it so square and so serious that adults would find it amusing and kids would go for the adventure.”

One of Dozier’s secret weapons for winking at a knowing adult audience, was casting fading industry stalwarts as Batman’s principal foes. Thus for Joker he tapped Cesar Romero, a veteran of dozens of Hollywood B movies and TV series whose roles had tended towards the suave ‘Latin Lover’, and who, for the adults in the room, was a beloved trash icon of his own.

Romero’s playful Joker, who appeared in a couple of dozen episodes over the show’s three year run, was perfectly at one with the comic books’ Joker of that muzzled era, a mostly harmless figure of fun complete with his own array of gadgets. Romero, perhaps indicating the seriousness with which he took the character, refused to shave his moustache, leaving make-up artists to cake on the white slap and making it appear if Batman’s most dastardly foe had somehow acquired a small patch of Artex under his nose.

It’s common to frame Tim Burton’s 1989 reboot, with Michael Keaton as Batman and Jack Nicholson as Joker,as a daring departure from the campery of the TV series. But with increasing distance it looks not so much a disruption of Dozier’s 1965 strategy as a big-budget sequel to it: Nicholson’s larger-than-life celebrity (and rumoured $100 million payday) mapping onto the flamboyant character of the Joker while winking wildly at those of us old enough to remember Chinatown.

“The casting of Nicholson was clever I suppose, it brought in people who weren’t Batman fans, but I don’t think he was good casting for Joker,” says Brooker. “Nicholson’s presence overwhelms everyone else including Michael Keaton. I might be being pedantic, but it certainly didn’t look like the Joker in my head. The Joker is very lean, he’s spindly and sinister.

He has a long drawn out face. Nicholson has the wrong look – too solid looking. I remember seeing it when I was 19 and being disappointed.”

Brooker and everyone else would have to wait nearly 20 years for a Joker who would do anything but disappoint. And if Heath Ledger didn’t look like the Joker in your head, for good or ill, he soon would.

In 2008, when audiences finally witnessed Heath Ledger’s heavily teased performance in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, there was a certain frisson of appropriateness to a man in a mask being played by a man who wasn’t there. Ledger’s death six months previously, of a prescription drugs overdose, seemed to give the film a darkly thrilling edge, a tincture of grim reality that meshed perfectly with Nolan’s stated intend to midwife the most realistic depiction of the Batman story ever told.

Rumours of Ledger’s death in some way being connected to his investment in the role, that in playing Joker he had touched some inner darkness that overtook him, are almost certainly without merit.

Ledger was by all accounts a party animal well before The Clown Prince of Crime came into his life. What’s certain is that, in a performance which may turn out to be definitive, and for which he was posthumously given an Academy Award, he put a wrecking ball through both the ’60s T.V. series and Nicholson’s interpretation, conjuring a Joker for the modern, post 9/11 age: a nihilist terrorist with no stated motive other than chaos and suffering. “Some men just want to watch the world burn,” as Michael Caine’s Alfred remarks.

The touchstone for Ledger’s interpretation most often cited is Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s The Killing Joke, published in 1988. The Killing Joke would subsequently become something of an embarrassment to D.C, its callous treatment of Barbara Gordon, the story’s only female character who exists merely to be mutilated by Joker, quickly soured with critics (if not with readers: in 2016, nearly 30 years after years after its publication, it remained D.C’s top-selling title in the bookstore market). Moore himself has all but disowned the story.

But the shrieking intensity of the Joker he and Bolland sketched, his balls-out insanity and taste for random homicide, remained and certainly seems to partly inform Ledger’s performance.

But in fact the real groundwork for Ledger’s triumphant reimagining had been laid a decade before in 1973 by Dennis O’Neal and Neal Adams. After his virtual absence from the comic books for nearly a decade their seminal story, Joker’s Five Way Revenge, took advantage of the weakening of the Code, and forced Joker into a modern milieu.

“From the darkness of a country road somewhere not of Gotham City, and from the greater dark of a past filled with evil . . . comes a terrifyingly familiar face!” screamed the cover page. This was a Joker who had bothered to shave his moustache.

“They produced an early 1970s take on what they thought Kane and Finger and Robinson were originally doing,” says Brooker. “They made it a much more Dirty Harry, Serpico early ’70s thriller. It took Batman and Joker back to the street, it feels more like a crime drama. But their Joker is a huge shift from Cesar Romero, and it’s the origin, really, of the Joker of The Dark Knight, The Killing Joke, Heath Ledger, every other Joker since.”

Nolan’s film also owes a debt to O’Neal & Adams’s re-assertion of the dreadful co-dependence of the characters, Ledger’s anguished cry of ‘I wish I knew how to quit you’ from Brokeback Mountain three years before finding a strange echo in the toxic obsession Joker and Batman have for each other in Nolan’s The Dark Knight.

Ledger’s performance left a thirst for the character which hasn’t been as intense since the heyday of the 1940s and which Jared Leto’s damp squib of a rendition in last year’s Suicide Squad did little to sate. News then, that none other than Martin Scorsese is to executive produce (though not direct) a Joker origins tale, and that Scorsese regular Leonardo DiCaprio is eyed for the lead, might seem to be thrilling news. But there is already a definite unease about the idea amongst the bat cognoscenti.

“One of the strengths of Heath Ledger’s Joker is that he won’t give us an origins story,” says Will Brooker. “He gives various versions. And what does he want? He doesn’t want money, he has no sexual desires, he comes from nowhere, we don’t know who he is at all. And Batman simply can’t deal with him. That to me is a spot-on Joker.”

But if nothing else the Scorsese/DiCaprio project proves that Joker, a character who was only meant to last one issue nearly 80 years ago, is going to be grinning at us from the shadows for a long time to come. Sometimes one way. Sometimes another.

Get the Esquire Newsletter. Click here to sign up