If you didn’t know already, nothing about Daniel Ricciardo would make you think that he’s a Formula One driver.

He is medium height, has olive tanned skin and a mess of curly hair that looks it has long since won the battle of trying to be tamed.

The 30-year-old is strikingly handsome, with a low-key demeanour, sporadic forearm tattoos, wears low-top Vans sneakers, skinny black jeans and a broad toothy-white grin. You would be forgiven for thinking he spends his days as a barista making almond milk flat whites at the most hipster of coffee shops.

The slight giveaway that there is something special about him is the Patek Phillipe Nautilus on his wrist. But even with the calling card of a luxury-calibre watch peeking out from under his sleeve, you’d probably assume he was tech start-up whiz kid rather than one of the world’s elite racing drivers.

“The thing is, F1 is a helmet sport,” he says in his thick Australian twang that throughout the day becomes peppered with accidental profanities. “Half the time you can’t even distinguish the helmets, let alone the drivers!”

If people just flick on the TV and see cars just zipping around a track, there is little connection to those behind the wheel. You see the winners, but you rarely get to see much more of them than lifting a trophy on the podium.”

“For fans to really embrace you, they need to see a human element— something that they can relate to and get behind.”

That ‘human element’ is one of the major cards that Ricciardo has over most of the other drivers in the paddock. In the hugely popular Netflix documentary series Formula 1: Drive to Survive, Ricciardo’s likeability and sense of humour is clearly evident.

“The thing is, F1 is a helmet sport, Half the time you can’t even distinguish the helmets, let alone the drivers!”

In a sport where a microsecond is so often the difference between victory and heartbreak, the stereotype of a successful racing driver is that of an unrelenting, data-driven semi-cyborg with a chip on his shoulder.

Ricciardo, by contrast, is cheeky, opinionated and has that most rare quality in a sportsman: genuine wit.

He listens to hip-hop, he watches UFC and he will happily spend an entire day off-grid, mountain biking. He may be a bit rough around the edges compared to the typical driver prototypes, but that’s what makes him the guy that you want to hang out with once the post-race champagne corks are popped.

It is worth stressing that anyone who underestimates Daniel Ricciardo does so with consequences. On the back of his helmet is the emblem of a honey badger, in reference to a nickname he picked up early in his career due to its reputation as being one of the most fearless species in the animal kingdom.

“He’s cute and cuddly, but as soon as someone crosses into his territory in a way he doesn’t like, he turns into a bit of a savage,” he explains.

With 29 podium finishes and seven Grand Prix victories to his name, Ricciardo is a proven race winner. So much so that last year he took the somewhat shocking decision to leave the comfort of a competitive (and race-winning) car at Red Bull Racing after four years, in order to spearhead a revival at the Renault F1 Team.

Unfortunately for both Ricciardo and Renault it was a gamble that didn’t instantly come off. His first season was hampered by a slower than anticipated car, on-track racing incidents and ultimately a below-par ninth-place finish for the Australian in the driver’s championship.

“Renault has taken a risk by investing so much in me, so I do feel that I have a big responsibility.”

This season (which starts this month with the Australian Grand Prix on March 15, and Bahrain Grand Prix on March 22) is a pivotal one for Ricciardo. Brought in at great expense—his two-year contract with Renault is estimated to be capped at a massive $55 million—to be the man who will help catapult the former championship-winning team out of midfield mire and back into podium contention.

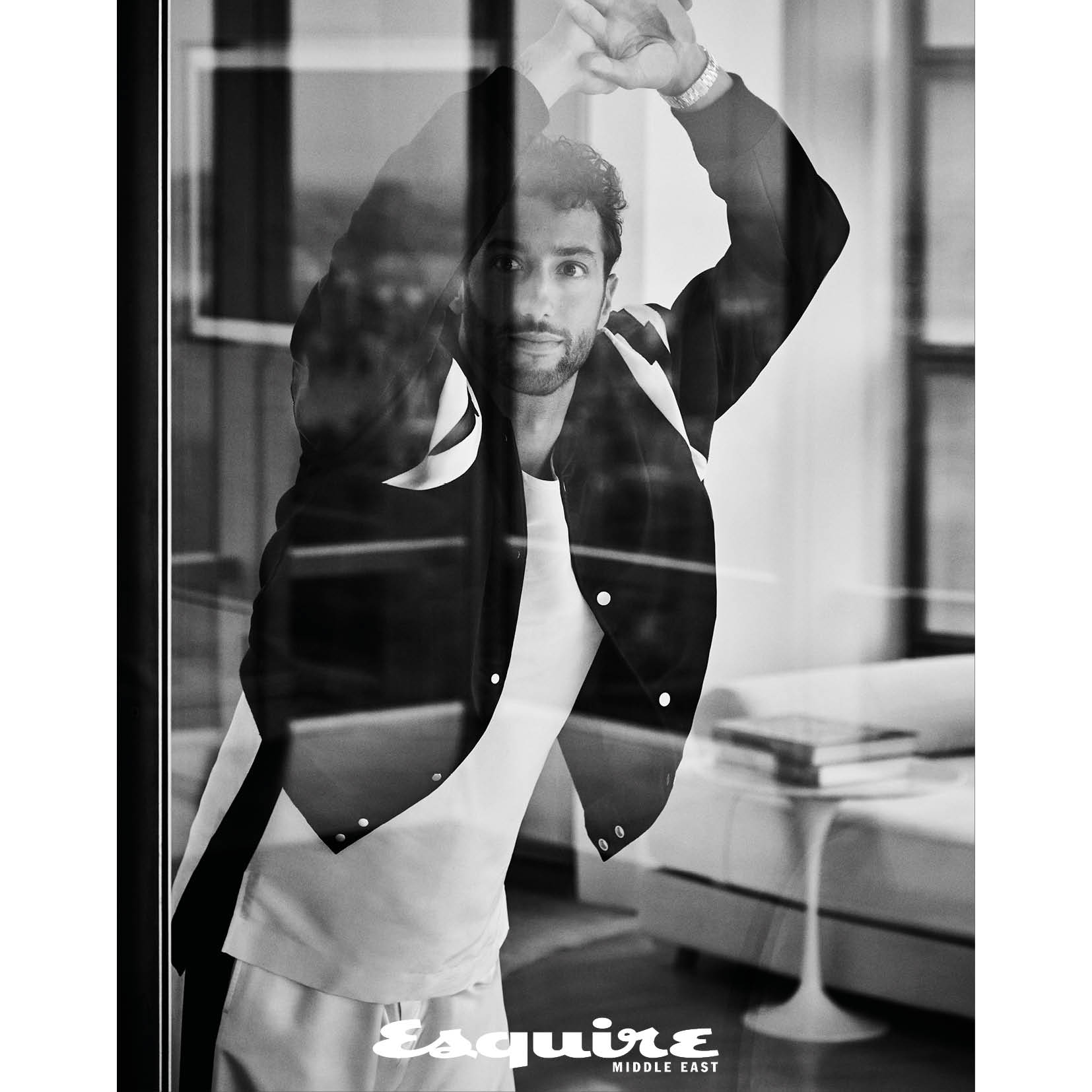

If the pressure of the upcoming season has being cranked up a notch, it doesn’t seem to be affecting him. Ricciardo arrives at Esquire Middle East’s New York City shoot location with little fanfare and heads straight to the floor-to-ceiling windows of the stunning duplex penthouse in One Beacon Court—just off Manhattan’s ‘Billionaire’s Row’.

“Woah, the view is sick!” he says to no one in particular as he gazes out across Central Park, 51 floors above the city streets.

“I’m going to have to sit with my back to the window otherwise I’ll just get distracted,” he laughs, plonking himself down in an armchair still wearing his oversized Givenchy coat. As we chat about his appearance on The Daily Show with Trevor Noah the night before, his business manager, Blake Friend—with whom he seems to have developed a somewhat telepathic form of communication—comes in to the room and puts a big bowl of mixed fruit and a green tea down in front of Ricciardo. “Dan can get a bit peaky if he hasn’t had something to eat,” says Friend.

Rather than peaky, Ricciardo seems relaxed. Since the final race of the 2019 season in Abu Dhabi, he has spent the majority of a two-month break between his house in Los Angeles and his family’s home in Perth. “I just really love the sunshine,” he quips.

He explains about how it is important to switch off from all the pressures of the racing season and, actually, until the Renault team unveils its new car for the 2020 season the main thing he can do is just get himself into a good place both mentally and physically to improve on a disappointing season.

“Going into last year, everyone was saying that I took a risk by leaving Red Bull and joining Renault. But it goes two ways.”

“It is a constant learning curve when it comes to a driver maximizing the car’s performance.”

“Renault has taken a risk by investing so much in me to help get them in a better place, so I do feel that I have a big responsibility.”

During the off-season the Renault team acknowledged that it needed to make some changes in order to give its prized possession a car that can compete at the level he is accustomed to, making changes in some of its personnel and revamping some of its ideas.

“There are a lot of things that will be better this year. And that’s even before touching on whether the car will be better or not,” he says. “I know the team now, I have a better relationship with my engineer, and even getting into the new car will instantly feel more familiar than it did last year.”

In a sport that is so often dominated by the fastest car (see: Mercedes’ dominance over the past six years), the big question from casual racing fans is normally how big an impact does a driver actually have on a team’s performance?

“The truth is, F1 drivers, don’t actually get much time behind the wheel of the cars. It’s not like we take them home and practice,” he says.

“The first time we drive the car is in February, and the last time we drove one was at the end of November. Throughout the year you only really get to drive it for three days every couple of weeks, so it is a constant learning curve when it comes to a driver maximising the car’s performance.”

“I feel that a driver will never finish his career feeling like they have ever really perfected the sport.”

With rule changes, developments in technology and new design regulations tweaking the sport every year, in essence the drivers have to rely heavily on personal experiences and spending time analysing data in order to improve.

“I had a really big year in 2014, where some things worked well for me,” says Ricciardo. “But I know I need to evolve rather than just think that I need to re-do what I was doing back then.”

“That driving style was awesome in that car—but maybe I need adapt a different style even with this one, even if I am not entirely comfortable with it. It is something that I need to learn and figure out.”

Showing a window into another one of these off-track interests, Ricciardo compares his job to a shooting a basketball.

“If you shoot 1,000 shots a day from a young age, you are going to peak at an earlier stage in your career, but with racing cars, the time behind the wheel is so sparse that the more you do it, the more you learn. I feel that a driver will never finish his career feeling like they have ever really perfected the sport,” he says.

If a Formula One career is just one long learning curve, then a particularly steep section of it for Ricciardo came about it last year at the Azerbaijan Grand Prix when not only did a unsuccessful overtaking manoeuvre on Toro Rosso’s Daniil Kvyat lead to both drivers overshooting a corner, but Ricciardo then reversed directly into the driver’s car effectively eliminating them both from the race.

“Sometimes it’s easier to manage donkeys than it is to manage drivers,” says Red Bull Team Manager, Christian Horner”

“That incident made me look like an idiot,” says Ricciardo. “The frustrating thing is that after an incident like that you have to wait until the next race to get the people to believe in you again. It’s like, I want to tell everyone ‘today sucked and I made a mistake, but trust me it is going to get better’. Sometimes you have to suck it up, wait to prove yourself at the next race. No one is ever going to have 20-plus races with no mistakes.”

In the last decade, only three drivers have won the Formula One world championship. Remove Nico Rosberg’s ‘one-and-done’ win in 2016, and the crown has either gone to Lewis Hamilton (5) or Sebastian Vettel (4). But sustained periods of one-or-two team dominance has long been a part of the sport and is often used by critics to label the sport as ‘boring’.

“I don’t think it’s a boring sport at all,” says Ricciardo. “Sure, I wish every race was great to watch and, the truth is, you do get some boring ones. Hell, I sometimes get bored during a race! But that’s the same in any sport. How boring is a nil-nil game of football?”

Ricciardo cites the introduction of the DRS (Drag Reduction System) on Formula One cars as something that has created more opportunity for overtaking and battles, and the current proposal to introduce budget caps for the teams in 2021 that will try and level the financial playing field. “I don’t think the sport is in a bad place at all.”

In the new season of Netflix’s Formula One: Drive To Survive, significant focus is given to the rivalry between Ricciardo and McLaren driver Carlos Sainz Jr.—the driver who lost his seat at Renault to make way for the Australian.

With so much on the line in a billion-dollar sport that pits racers from around the world directly against each other—not just on the track, but also with the right to drive one of the 20 F1 cars—the rivalries can be quite explosive.

“I remember Kimi [Räikkönen] used to give me the cold shoulder and I took that personally”

Ricciardo is no stranger to the odd on-track skirmish. At Red Bull there was more than one racing incident between him and his teammate Max Verstappen, notably in Hungary in 2016 and Azerbaijan in 2018, both times Verstappen crashing into the Australian’s forcing him out of the race.

The friction between the two teammates even had Red Bull Team Manager, Christian Horner, declaring that “sometimes it’s easier to manage donkeys than it is to manage drivers”.

But for Ricciardo, rivalries and racing incidents are very much part of the job.

“Ultimately each driver believes that they are better than the guy next to them,” he says. “On the grid, I tend to be quite friendly with people, but if I smile at someone and they blank me—it kind of pisses me off. I take it personally for sure.”

Refusing to be drawn into which specific drivers on the grid he believes “have a chip on their shoulder”, he does recall a time from his first few years in Formula One that has stayed with him. “I remember Kimi [Räikkönen] used to give me the cold shoulder and I took that personally. I would make a mental note of it, and on-track if I was ever feeling generous it was never going to be towards him,” he laughs.

While perhaps the root of his generosity on track may be questionable, his generosity away from racing isn’t.

The recent bush fires that ravaged enormous parts of Australia struck a personal note for Ricciardo, who was quick to commit to working on ways to make a lasting impact on the communities affected in his home country. He has pledged to donate the proceeds of auctioning his signed racing suit from this month’s Australian Grand Prix to bushfire victims.

“Ultimately each driver believes that they are better than the guy next to them.”

“The scale of it is mind-blowing, and it’s going to take a long time for things to be fixed,” he says, leaning forward in his chair and taking a more stern tone, explaining how it’s imperative to look at the long term impact of the bushfires.

“Just because the news stops reporting on it, it doesn’t mean that everything is fine again. There are whole communities that are completely devastated, so we’re going to be doing stuff throughout the year to keep everyone positive.”

At that point, the penny drops. The Daniel Ricciardo who stormed into Formula One a decade ago like desert rain, winning over a legion of sports fans with his laid-back attitude, infectious charisma and fearless driving style is still very much there, but he has evolved.

He didn’t run away from competition at Red Bull; he wanted, no, he demanded more responsibility. He wants the challenge of dragging Renault back to the mountain top, just like he wants to help his country recover from the bushfires. The biggest risk of his career wasn’t fuelled by greed or guarantee; it was fuelled by maturity and a mission.

You may not guess that Daniel Ricciardo is an elite level racing driver when you first meet him, but he’s fine with that. And it certainly isn’t going to stop him.

Bahrain Grand Prix, March 25. bahraingp.com

Photographer: David Needleman

Stylist: Corey Stokes

Groomer: Jessica Ortiz at Forward Artists

Production: NM Productions

Location: Penthouse 51/52W at One Beacon Court. Listed by Erin Boisson Aries of Christie’s International Real Estate for $34 million, this exclusive 5 bedroom/6 bathroom, 9,000 square foot duplex home boasts extraordinary panoramic views of Central Park, Uptown and Downtown Manhattan, the East River and beyond. www.christiesrealestate.com